Dana and I went out to Thai food on Grand Avenue the other day, and happened to sit next to one of my heroes. Later I wished I had said something really thoughtful and articulate like, "Excuse me, I apologize for interrupting your meal, but I couldn't let you leave without telling you how grateful I am for the work you've done to support the liberation of African American people, and of all people, and for the many very real sacrifices you've made over these many years. Thank you." Of course, if I had actually talked to her in the moment, whatever I said would have come out making me sound like a gibbering stalker, (I know this to be true because I ran into her once before, and did talk to her like a gibbering stalker), so it's for the best that I contented myself to bask in the glow of her fashionable (although in no way ostentatious) back, which was seated only a foot or two away from me.

I doubt she's recognized much now, but Ericka Huggins spent a few years being infamous. In 1970, she was a defendant in an internationally notorious and highly politicized murder trial in New Haven, Connecticut. Folks like Dr. Benjamin Spock and writer Jean Genet came to Yale to speak on her behalf. One year before that trial, her husband John Huggins, a leader in the Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panthers, was killed at UCLA by members of a rival activist faction. Throughout the 70s she co-authored a book of poems with Huey Newton, held political offices, and directed a Black Panther school. I wish I knew more about what she's doing now – meditation, spirituality and education seem to be among her current interests, and she does some speaking about her time in the Black Panthers, but it's hard to find out much about her because, although one site says that she's writing a memoir, she clearly isn't out to promote herself, which is a consistent theme for her, actually.

Ericka grew up in Washington, D.C. She was politicized early on, attending the March on Washington when she was 15. The late 60s, the moment when Ericka was coming of age, was a point of increasing militancy among activists in general, and Black activists in particular. (SNCC for example, a major organization in the Civil Rights Movement, officially changed its strategy from specifically nonviolent, to including a broader range of tactics when Stokely Carmichael took over the organization in 1966.) Like thousands of young people around her, Ericka probably felt shocked and horrified by the poverty and violence that Black people and poor people were experiencing around her. Race riots were a regular feature of the late 60s, and were invariably inspired by, and then followed by, harsh police violence. The Vietnam War, and protests against it, escalated around her. Internationally, militancy seemed to be on the increase, with revolutionary movements gaining prominence in Palestine, Northern Ireland, and even next door in Quebec. In this context, in 1968, Ericka joined the Black Panthers. She met John ("Jon" in Ericka's love letters) at college and they moved together to LA where they got very involved in the growing Panther chapter there. They took and then taught political education classes, organized, fundraised, served in the Party social programs, and I'll assume they studied marksmanship, a requirement for all Party members. John took on a leadership position. Ericka got pregnant.

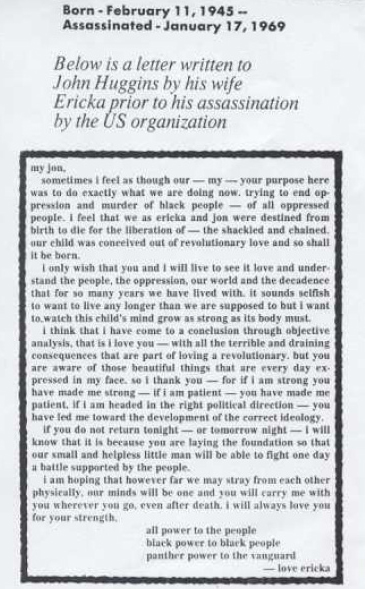

With his beard and bellbottoms, John gave off much more of a hippy vibe than his fellow militants, especially Bunchy Carter, a charismatic former gang leader who was a rising star in the Party (and was known for his impeccable style), and who was with John on the day they met with, and then were shot and killed by members of the US organization at UCLA. I won't pretend that the details of this story aren't complicated*, but one thing we do know from 1975 senate hearings on the FBI's counterintelligence program (Cointelpro) is that the FBI actively sought to increase tension between the Panthers and US**, before and after these killings, by sending inflammatory cartoons and letters to both organizations, and by propagating rumors about each organization. I've read that Richard Held, the FBI officer in charge of the L.A. office at that time took credit for the deaths of Huggins and Carter. I can't back that one up with a citation though.

After John's death, Ericka moved with her daughter Mai to Connecticut where John's parents lived. With local activists, she started a Panther chapter in Bridgeport, and then moved it to New Haven. She was 21.

In her memoir, A Taste of Power, Brown remembers Ericka as being checked out and disconnected after John's death. An interview with a Connecticut Panther in another memoir - David Hilliard's This Side of Glory - describes her as "spaced out but genuine". I don't know why she kept sleepwalking through her activist career at that point. Maybe if your partner is killed for the revolution, you feel you must soldier on, to give his memory meaning. Especially because, as she trudged through what must have been a personal nightmare, the bigger community was turning uglier around her too.

John Huggins was killed on January 17th, 1969. That night, the LAPD raided John and Ericka's home and arrested all twelve Panthers inside, including Ericka with their infant daughter. There were no real charges filed against those arrested – the LAPD justified the arrests by saying that they were preempting retaliatory action towards members of US. This kind of police action towards the Panthers was typical. They raided Panther offices across the country frequently, and often repetitively, sometimes looking for specific suspects, sometimes just to destroy their typewriters, or break up their free breakfast program, which the FBI specifically sought to destroy. (Details on that here. Just search for "breakfast".) In April of '69, 21 New York Panthers were arrested and charged with conspiracy. All 21 were eventually found innocent. Also in April, the Des Moines Panther office was leveled by a bomb blast, injuring two Panthers. In response, local police arrested Panthers. In the first two weeks of May that year, the LAPD arrested 42 Black Panthers. Of course, this hostility wasn't one sided. The Panthers were both a service organization and a militant one, and as much as their free clothing, free food, free medical clinics, ambulance service, and free breakfast programs have been underreported, their armed confrontation of police was also quite real. Panthers regularly engaged in shootouts with police, and not all these were initiated by the cops. After all, the Panthers were trying to engage in a revolutionary struggle.

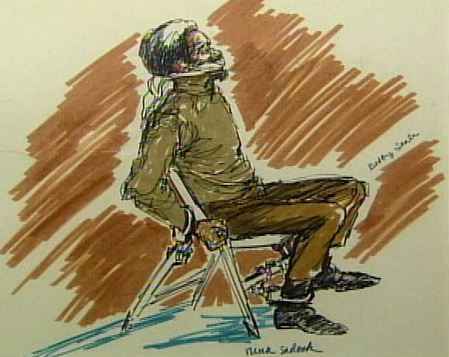

Outside of the Panthers, even mainstream liberals were aware of how harsh the repercussion could be for activists who opposed the status quo. In August of 1968, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley had sent 12,000 police officers and 7,500 National Guard in to disrupt protests at the Democratic Convention. (Bobby Seale, the Panther's co-founder and essentially second-in-command officer, spent several years fighting legal charges from the Convention protests. He'd famously been bound and gagged in the courtroom during his trial.) In December of 1968, more than 450 students at SF State were arrested in connection with a student strike in support of Black Studies program. And only a few months earlier, police had massacred hundreds of student demonstrators in Mexico City. Vietnam raged on. Nixon had just been inaugurated. Someone who was as involved in the Panthers as Ericka was in early 1969 must have been pretty convinced that the revolution was needed, that it was coming, that a new system of socialist governance prioritizing self-determination for Black people and economic fairness for all seemed like a real possibility. And militant struggle probably felt like it was the strategy for bringing that revolution.

Courtroom illustration of Bobby Seale, bound and gagged during the initial Chicago 8 hearings

It feels important to know all this context before you read what happened next. What happened next is that that someone, a Panther, murdered someone else, another Panther, a 19 year old from New York. And that young murder victim, Alex Rackley, was killed after two days of being tortured – having boiling water poured on his body and so forth. And Ericka was in the house where all this happened.

A mentally-unstable out of town Panther named George Sams instigated the kidnapping and torture of Rackley, who he accused of being an undercover agent. Several New Haven Panthers participated in the torture and then in the murder. Sams only did four years in prison for the killing, and rumors persist that he was an agent provocateur himself, although I've never read any evidence for this. He was certainly crazy, and was heavily medicated during his own trial. And it is unarguable that the Panthers were heavily infiltrated. Still, at the point when you are pouring boiling water on someone, or even watching your comrade pour boiling water on someone, you must take some personal responsibility. Going along with what you're told isn't any more justifiable for revolutionaries than it is for Nazis.

While it's not a justification, I'm sure that Ericka Huggins learned this lesson. After the actual killers were convicted (some confessed, turning state's evidence), she and Bobby Seale were tried for ordering the murders. They spent two years in jail in New Haven during the proceedings, inspiring an international protest movement.*** Yale students staged a months-long strike, starting with a massive May Day rally featuring Abbie Hoffman et al. While she was in prison, Free Jazz pianist Francois Tusques composed a song for her. (You can listen to it on this archived WFMU jazz show. The song starts roughly at minute 1:46 and then restarts at 1:48.)

What shocks me about Ericka Huggins, is that after seeing the absolute ugliest sides of revolutionary movements, she moved to the Bay Area and spent the 1970s working on the Panther newspaper, running for and then serving on the Berkeley Community Development Council (an anti-poverty agency) and on the Alameda County School Board, and eventually running the last surviving segment of the Black Panther Party – their children's school. She was, I guess, one of the last members of the Black Panther Party, since she continued to run the school throughout the 1970s until it finally closed in the early 80s, long after every other Panther institution was gone, and after Huey Newton, the organizations' charismatic but borderline leader had lost all credibility among activists and even most of his friends.

Another thing that strikes me about Ericka Huggins is the way she just doesn't show up in Panther memoirs. Elaine Brown, who named her daughter Ericka dedicates more page space to her than any other Panther alum. As far as I remember, everything Elaine says is positive, and even in her book, there's not much. In other memoirs, Ericka tends to show up for a few pages as a benign force and then disappear, as if she was never there. For someone who was so important in the Party, I can only guess that she found a way to stay out of everyone's way and for the most part, do the work that felt important, instead of engaging in power-plays or battles of ego.

Sitting next to her at dinner, I confess I had a difficult time paying enough attention to my date. What does someone who spent more than a decade trying to make the impossible work feel when it doesn’t? What does it feel like to be so key in a grassroots, militant, educated, disciplined, activist corps - a group that seemed so close to revolution – and then to lose it? Does she resent the way Panther leaders spiraled out of control? Does she feel defeated by the forces of the state – the FBI, the police, the media – that did, in fact defeat her movement? Does she feel manipulated? Is she angry? Her manner is quiet and poised. She projects a feeling of attentive calm. I hope she thinks back on serving free food to children, on writing and explaining, on teaching and running a school that provided a real alternative for kids who needed it and feels proud.

_________

That's how I ended this article. And I was just looking for a few more photos before posting, when I decided to start googling Ericka's name and the world "meditation" (since I know she's a practitioner) and found her to be associated with that ashram on San Pablo – Syda.

Apparently, the New Yorker did an investigation of Syda a few years ago, and quoted members who reported sexual and financial abuses within the largely secretive organization. Former members complained that they were harrassed if they spoke out. There's a website where ex-members share their (bad) experiences, although for the record, most of the alleged abuses happened quite a while ago, and even the New Yorker article points out that most members have no contact with the people at the top of the organization, and simply go to Syda's various ashrams to meditate, chant, and find spiritual community. At this point, I'm feeling a bit depressed by imagining my hero as a cult member. And I'm sure it's more complicated than that anyway. I guess I shouldn't be surprised that she can stomach a degree of unquestioned hierarchy, since she managed to work under an abusive power fiend like Huey Newton for so long.

I really admire Ericka Huggins. I'm not an investigative reporter, and if I was, why would I want to 'expose' someone who has spent most of her life working for good? So what if she likes charismatic leaders? I want to respect the fact that she has a life. Has some privacy. So good luck to you Ericka. I'm not going to read any more about what you did or what you do. Thank you for your work. Good luck to you in your life.

_______________

*Trying to make out what really happened here is completely impossible. Every Panther has their story, and the stories tend to contradict each other.

**Every December I subject some poor soul to my annual anti-Kwanzaa rant. I know that if the holiday has come to have meaning for people, I should support it, but for me it is uglied by the fact that it was created by Ron Karenga (or, as he named himself, Maulana – a Swahili word for master teacher). Karenga was the head of US at the time of the UCLA shooting. He went on to serve prison time for assaulting and torturing two female members of his organization.

** As usual, Snopes does a nice job of clarifying the line of bullshit that circulated on the net a few years ago suggesting that Hillary Rodham, a Yalie, was Ericka's defender. (As if Hillary would have advocated for militants!

If you're not done already with learning about Ericka:

I mentioned it a bunch of times because A Taste of Power talks more about Ericka than most published material on the Panthers. The author, Elaine Brown, has been accused of including some inaccuracies, or maybe outright lies in this book, but it is as good a history of the Black Panther Party as any, and, coming from a woman's perspective, manages to be honest about some of the disparities that did exist in the organization.

Most of what I know about Ericka's trial comes from the long out-of-print Agony in New Haven, which was certainly descriptive. It seemed to depict the four month long jury selection process in real time, detailing each potential juror, each recess called by the judge, and each outfit chosen by the various lawyers. Well written, but only worth while if you're obsessed. There's a newer book I haven't read yet called Murder in the Model City which probably provides some more context.

I know he's become controversial, even among radicals, but Ward Churchill's Agents of Repression (written with Jim Vander Wall) is still the most readable, detailed, and footnoted book I know about Cointelpro and it's where I first learned anything about the Panthers. I recommend it.

Finally, the very best website for Black Panther information is It's About Time. This site has tons of original source material on the Party: newspaper transcriptions, dozens of photos, regional chapter histories, and updates on issues impacting former Panthers now. Most of the photos in this post came from that site (thank you!) and I haven't even gotten half-way through all there is to read there yet. Check it out.

Note that I've made a couple small factual and editorial corrections and changes since I first wrote this, although the post is pretty much the same as the original.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

9 comments:

Cult issues aside, you should check out the Alexander Street Press collection of Black Panther documents. They charge tons of money, so it looks like the only schools that have it near you are:

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIV, FULLERTON SAN JOSE STATE UNIV

SONOMA STATE UNIV

STANFORD UNIV LIBR

Here's what's in the collection:

http://alexanderstreet.com/products/bltc.htm

It's all electronic, so you'll have to go to the library yourownself. But, it should be full of amazing stuff and easy to search.

Wow Annie, I'm lucky to have a librarian on my side! I'll most certainly check out that collection - I'd never heard of it before, but it seems right up my alley.

Wow, this was a wonderful article.

I am currently reading Elaine's A Taste of Power, and I am fascinated by the her story as well as the shared story of all the women in the BPP.

I found your blog when I was googled Ericka's name. I googled Ericka's name because I wanted to know what she's been doing, your article filled me right in!

Do you have any idea what Mai is doing? Did she follow in her revolutionary parents' footsteps. I'm actually more interested in her story as well as the stories of the other children of these Black militants. In Brown's book, many of the BPP women were pregnant during these chaotic years. I'd just like to know how the struggles of the parents affected the progeny.

Thanks for the information and great websites. Very helpful!

Hi Kana,

Thanks for visiting and I'm really glad you got something out of the blog. A lot of Panther kids do seem to be political - I've found a few on the internet. I've also learned since writing this that Ericka does quite a bit of public speaking about her time in the Panthers. here's a link for her speaking work.

It was great to read the wonderful tribute that you have written about a women who has, too, become a heroine in my eyes. I recognize that you've said you respect her privacy so I will not disclose of her whereabouts and what she is doing now. But as an individual who has been graced by her teachings, I'm going to go out on a limb here and say that she would probably love to hear your sentiments. She's a humble but very kind and open woman. Once in a while, she has shared information about her past and she does it willingly - I think to show the significance of its purpose. I do share your belief that she was an oft-overlooked quiet force within the civil rights movement. Next time you should run into her, I say you should approach her and commend her for her work. I've never seen her turn someone away and she's seemed genuinely appreciative of the feedback and support that she gets...

Thanks for posting this-- the detail and complexity was useful. It is hard to remember the brutality and counter-brutality of the sixties.

And creates a case of the importance of non-violence, and by extension, meditation; which creates a calm space for thinking and reflecting instead of crazy violence.

Post a Comment