Showing posts with label Chinese American. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Chinese American. Show all posts

1.15.2008

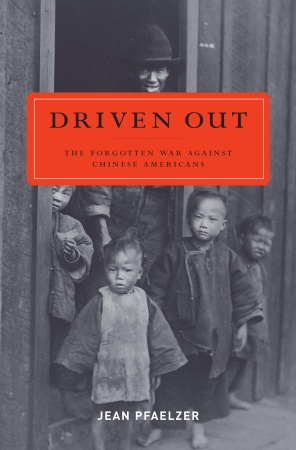

Driven Out

Since I started tracking visits to this site I’ve noticed one post gets more visits than any other. I wanted to pass on a related resource for folks who came here to read about the violence that Chinese-Americans faced in the Western United States throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Driven Out is the deepest, most thorough examination of that shameful piece of history that I’ve found. I’ll display a rare moment of agreement with the New York Times in saying that the book contains an unfortunate lack of analysis and narrative that would have made it better reading, but I still recommend this to anyone looking for more on the issue. Pfaelzer's research is strong and she looks unflinchingly at what she rightly calls pogroms of Chinese-Americans, citing case after case after case of legal and extra-legal violence and expulsion of Chinese immigrants. Its difficult reading, but worthwhile for the sake of understanding a long-suppressed history.

Labels:

1800s,

Asian American,

books,

Chinese American,

reviews

7.02.2007

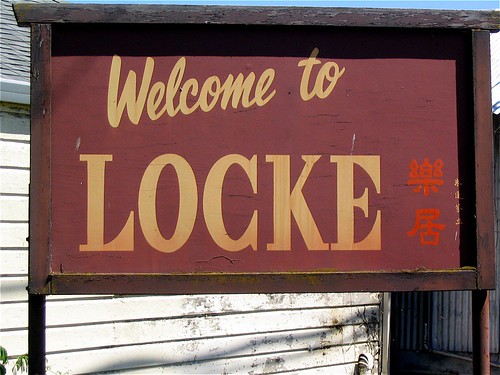

Locke, CA

Little Rutabaga and I left my folks' house in Sacramento on Sunday, and drove along the levee road, watching the river, and listening to an audio tape of Stuart Little, which probably doesn't need any advertising, but, in my opinion, should be regarded as one of the masterpieces of 20th century fiction. Little Stuart is as complex as any literary hero: he's gutsy and self-assured enough to win a toy sailboat race in his first time at 'sea', but also so proud that he misses his chance with the first woman he meets who shares his diminutive stature. At first I thought Stuart's predicament – as the mouse child of human parents – was a metaphor for homosexuality. Stuart is a bit of a dandy, meticulous in his grooming and manners, carrying a small cane within his first few weeks of life, and with none of the loud, messy habits of his 'normal' older brother, but I gave up that theory at the point in the story when he falls for the bewitching songbird, Margalo. Stuart's status as an outsider is a classic theme, subject to a number of interpretations, but I shouldn't try to make his story mean too much. I enjoyed it more when I was just enjoying the understated, dry storytelling of E.B. White. Please, no one tell me if he had some horrible skeletons in his closet because he was really super writer.

The tape ended (in a wonderfully ambiguous conclusion) just as Ru and I got to Locke, a small town in the Sacramento Delta that is still entirely made up of the wooden homes and businesses that were constructed there in the early 1900's. Some of the old buildings haven't been maintained much in the last 30 or 50 years, but most are still habited in one way or another. There are a lot of art galleries now, Al the Wop's bar (full of bikers) seems to be doing well, and the Locke Garden restaurant was very busy. Even though Locke is completely authentic in its original construction, it's not a tourist version of an oldentymestown. There are no Locke t-shirts for sale, no saltwater taffies, no spinning rainbow windsocks. For a few dozen people, Locke is just home.

I lived in Sacramento for 6 years, but I'd never been to Locke or any of the other agricultural towns in the Sacramento Delta. I'd never even driven through, and it's only about an extra half hour to get back to Oakland that way, along 160, the levee road, to Highway 24. At Dai Loy, now a museum but once one of a number of casinos in Locke, the attendant told me that she hears that all the time. Even folks who drive along 160 to Antioch don't stop much.

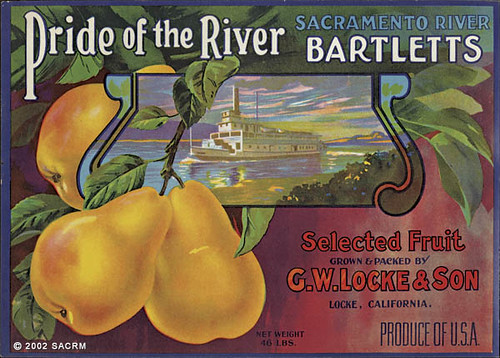

Of course, there's not so much to see while you're there. Locke is literally two streets and even though my parents warned me that it was tiny, I was still surprised. The houses and businesses are built neatly and closely in two small rows, maybe because in 1914 when Locke was founded, Chinese-Americans weren't allowed to own land, and the town founders had to lease their little chunk of property from George Locke, a white farmer who owned the land.

Actually 'grown and packed by' Chinese, Japanese, and Philippino laborers paid a dollar and maybe a meal for each day of work.

Locke is the only surviving all-Chinese rural town in the United States. It was built during the depression, after the Chinatown in neighboring Walnut Grove burned down. Unlike many Chinatowns where distinct ethnic groups of Chinese immigrants lived together, speaking different languages (dialects = languages, or at least, the difference between a dialect and a language is arbitrary), sometimes competing for control of various resources, Locke was settled and occupied almost exclusively by immigrants from the Zhongshan region in China. It lacked the tension that, in other communities, sprang up between competing and ethnically separate Tongs. (Kind of like competing mob families, Tongs tended to control the prostitution, gambling, and opium sales in the community.)

Gambling was a major part of Locke's economy. At one point there were 3 separate casinos featuring lotteries, various Chinese betting games, and later, Blackjack tables. Locke also had five brothels (at times the only businesses in town owned by white people) and during prohibition, a couple speakeasies.

Despite the vice-filled main street, lots of folks raised their kids in Locke. Most residents lived on the second street, behind the business district. With the river right there, kids had a great time fishing and swimming and playing outdoors. Because they were Chinese, most were forced into the segregated Delta schools (until WWII when the internment of Japanese-Americans reduced the number of students at the Asian schools to the point that they couldn't stay open). In the afternoons, after public school, Locke kids went to the Kao Ming School, where they got instruction in their language and culture. The school went through a couple incarnations, and finally closed permanently in the '80s when there weren't enough Chinese kids around to keep it going.

Martha Esch painting the old Star Theater. She's got a gallery in town and hosts studio painting sessions and other events there.

Rutabaga and I spent a couple hours in Locke, eating Mu Shu vegetables at the Locke Garden Restaurant (housed in the town's oldest building), and checking out the art galleries and bikers. I'm not sure if bikers are a regular feature of the town or of this was just a big rally weekend. Feel free to let me know members of the biker community. The streets were surprisingly full for such a little place, but of course nothing like in its hayday.

At its peak, Locke had hundreds of residents. During pear season, and on certain weekends, more than a thousand people stayed in the rooming houses, gambled in the casinos, ate at the restaurants, and shopped in the markets and dry goods stores. Now, the Chinese populations is around 10. I saw one Chinese-American guy in town, a biker at Al the Wops. Most all of the young people of Locke moved away to bigger cities – many going to college and mainstreaming into the larger culture. The folks who stuck around got older. Most have died.

I just finished reading a lovely oral history of Locke, with photos accompanying the stories of the elderly residents. Written and photographed in the 70's and early 80's by James Motlow, a white guy who had lived in Locke, along with a co-writer Jeff Gillenkirk, and Connie Chan, a Locke native who worked as their interpreter for the project, Bitter Melon presents a range of experiences: the relatively successful men who got work as foremen or ran the local businesses, the women who worked in local canneries and often had to leave their kids to fend for themselves, and the dollar-a-day laborers who never made enough to get married and start families, go back to visit parents in China, or to move out of the little town as it shrank away.

In the 80s, a Historic American Buildings Survey documented the town. The whole report is worth checking out, especially the photo series of the town.

Finally, and I probably should have put this first, you should check Locke's own website. You can see photos of just about every building, and read about the galleries and historic sites that are there now.

The community garden behind the town of Locke, from the Historic American Buildings Survey of the National Park Service.

On the way back to our car, Rutabaga and I passed a family trying to resolve some engine trouble outside of their home on Locke's second street. They seemed to be immigrants too, Latin American not Chinese, as Mexican and other Central American immigrants are now the main laborers along the Delta and throughout our country's agricultural sectors. A couple of visiting painters were packing up their little canvases of Locke's scenic buildings and getting ready to drive off too. Ru and I pulled out onto the road. Not north (like Stuart Little), but (like him) I somehow felt I was headed in the right direction.

Labels:

Asian American,

Chinese American,

delta,

farming,

labor

6.26.2007

S.F. Shootout

I'm glad that I'm not a professional historian because if I were, I might have to find some other way to express this: Dennis Kearney* was an utter ass-wipe. An immigrant himself, Kearney founded California's briefly influential (and highly racist) Workingman's Party. He made a political career out of the thoughtful slogan, "The Chinese Must Go". His fiery speeches were quite radical – he advocated lynching of wealthy business owners – but he wasn't marginal. His political ally, Isaac Kalloch, became San Francisco's mayor in 1879.

That is disturbing, but not surprising. Here's the crazy part: in the 1870s, the founder and editor of the Chronicle, Charles de Young, railed against Kearney and Kalloch (then only a mayoral candidate) in his paper. I haven't read the editorials directly – anyone know of where I can find those archives online? But from what I understand, de Young wasn't particularly concerned with Kalloch's racism, but more with his popularity. Trying to undermine the mayoral candidate, he publicly exposed a sex scandal that Kalloch (a Baptist minister) had been involved with in another state. Kalloch ridiculed de Young right back and from the pulpit, calling de Young's mother "whore-mongering", and then in retaliation de Young, the editor of the Chronicle, shot Kalloch, the mayoral candidate!

Kalloch survived, and won the election in part because of the sympathy he garnered for his injury, but a year later his son, defending the family honor, fatally shot de Young. He admitted to the shooting but got off free. Fortunately, Kearney's Workingman's Party faded shortly thereafter, but Kalloch did fine, serving two years as mayor.

*Note that Wikipedia reveals that Kearny Street, which runs right through Chinatown in SF is not actually named after Dennis Kearney. This information comes as a relief, but I wasn't too excited to learn who it was named after: Stephen Kearny, who founded of the US Cavalry and used those troops to expand white US occupation into Native American homelands in the Western part of the continent. He went on to command a number of battalions in the Mexican-American War, winning California for the US of A, which, I imagine, is why he got a street named after him in San Francisco. Related: we can also breathe a sigh of relief that Geary street is named after a former postmaster, not California Congressman Thomas Geary, who wrote an 1892 law extending the Chinese Exclusion Act, and expanding it to require Chinese-Americans to carry permits at all times, or risk deportation or punishment by hard labor. His act also denied habeus corpus to imprisoned Chinese-Americans, removing their rights to ask a judge to review the legality of their detentions. If you want to know who any other SF streets are not named for, look at this site.

Labels:

1800s,

Asian American,

Chinese American,

labor,

newspapers,

racism,

SF

6.25.2007

Anti-Chinese violence

I’m going to do a few entries about the history Chinese-Americans in the Bay Area, and the relationship between the white labor movement and Chinese workers. It's been pretty disturbing reading about this stuff. I had a sense of some of the racism that was historically directed at Chinese immigrants, but I certainly didn't understand the scale. The most appropriate word to describe what happened to Chinese people here is probably 'pogroms'. I grew up here in California, and I definitely didn't learn about any of this in school. Anyway, here's the first post – about labor:

During the Gold Rush, prospectors, mostly men, flooded into San Francisco from all over the world. Most came from the Eastern United States, but also from outside of the country, especially Chile and China. Chinese gold-seekers made up a significant portion of the new 'settlers', setting up communities in San Francisco and in rural areas too.

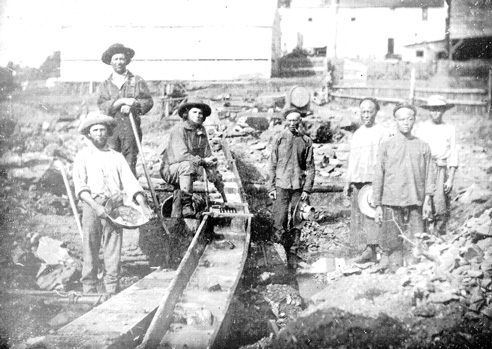

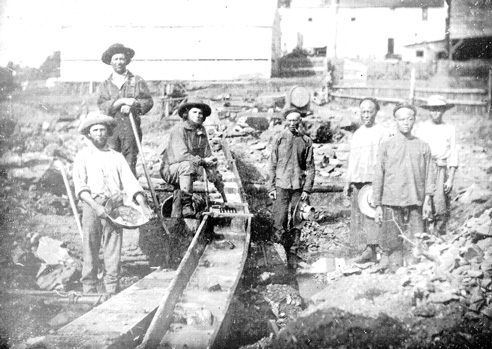

This 1852 photo by J. B. Starkweather shows a rare site: Chinese and European Americans working together in a gold mining operation.

Over the next few decades, Chinese immigrants became involved in a wide-range of work: Rurally, Chinese settlers created the fishing industry here, established agriculture in the Central Valley, and worked as laborers building the levee systems on the Delta, almost always living in isolated, Chinese-only communities. By the 1860s, 2/3 of the laborers building the Western portion of the transcontinental railroad were Chinese men.

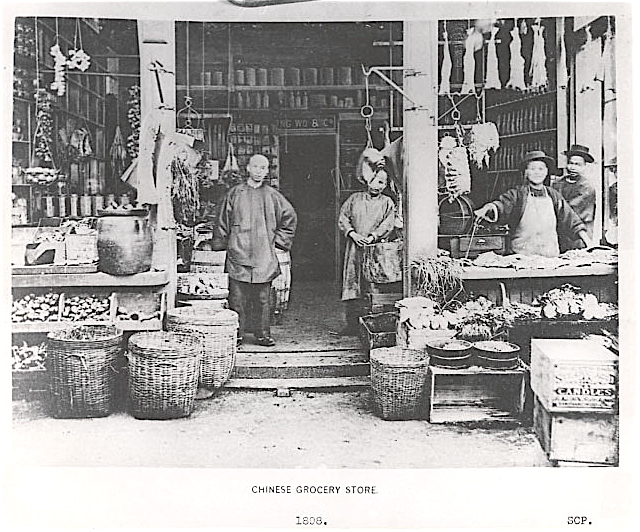

In urban settings, Chinese workers took jobs in just about every trade: manufacturing, building, and running small businesses including laundries, restaurants, markets, and repair shops. Around the Bay Area, traveling Chinese peddlers sold fresh produce out of large baskets that they'd carry from house to house, and later from the back of horse-drawn produce carts.

Like many immigrants, new arrivals from China tended to stick together in the same neighborhoods, seeking out and forming supportive associations with people who came from their same regions and extended families back home. But the segregation of Chinese men and women into Chinatowns wasn't just a preference of the residents there. It was mandated by law and required for safety.

It would be difficult to exaggerate the level of hostility and violence directed towards Chinese-Americans in the late 19th century. Before I started reading about this a few weeks ago, I had no idea how overwhelming and horrific this bit of history was: white Americans, encouraged by labor leaders and sometimes officially sanctioned by local governments, perpetrated a series of pogroms against Chinese communities throughout the late 1800s. A few examples:

- In 1871 in Los Angeles a brutal race riot left roughly 20 Chinese men dead, after white residents ransacked Chinatown there.

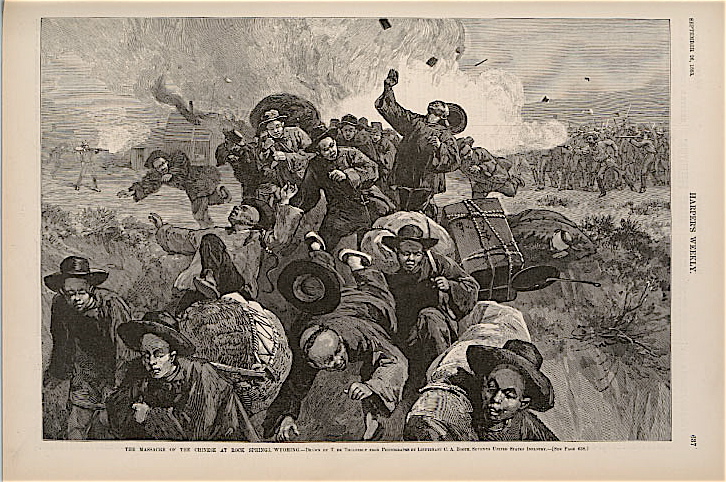

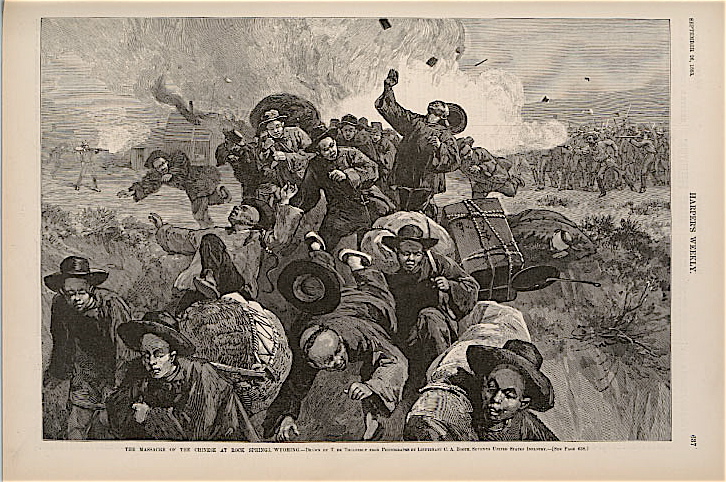

- In 1885, in Wyoming, European immigrant mine workers rioted against Chinese workers (who were paid less than white workers and who had historically been recruited as strikebreakers), killing 28 Chinese miners and destroying 75 of their homes.

- In 1886, virtually every Chinese resident of Seattle was rounded up in an attempt to remove them from the city.

- In 1887, 31 Chinese gold miners were murdered by bandits in Oregon, and no one was prosecuted for the murders.

"Massacre of the Chinese at Rock Springs, Wyoming" From Harper's Weekly housed at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Legal repression of Chinese immigrants escalated dramatically as the years progressed: By 1852, Chinese gold miners were subject to a significant foreigner tax that no other international miners were required to pay. Two years later, the Supreme Court of California extended to Chinese people a ban already in place prohibiting 'Negroes' and 'Indians' from testifying for or against white people. In 1872, Chinese people were barred from owning real estate or business licenses in California. And devastatingly, in 1882, Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring Chinese laborers from entering the country. This ban was generally applied to almost every Chinese person, making it impossible for example for Chinese men already living in the US to bring their families here to join them. (And because the immigrants who came here from China were almost exclusively male, and because the Exclusion Act prohibited anyone else from coming, the Chinese community dwindled as its bachelor class aged without raising children.) The Chinese Exclusion Act wasn't repealed until the 1940s and the severe immigration quotas reserved only for Chinese immigrants weren't ended until 1965. 1965!

Theorists and intellectuals fell over each other advocating for the removal of Chinese people from this country. Here's a fairly typical anti-Chinese screed of the time, devoted to the "Chinese Question". I confess, I didn't read this whole steaming pile of garbage, and instead skipped to the final chapter (starts on 196) titled "One course, and one course only, can stay the Eastward migration of the yellow race, and its gradual conquest of the land." You can guess what course that is. 'Progressive' non-Chinese thinkers tended to advocate for Chinese immigrants solely on the basis that they were willing to do the tedious, humiliating, or back-breaking work that white people were refusing to take. Hmm, sounds familiar.

Government leaders and others in the mainstream were certainly responsible for the legal sanction of racism here, but labor leaders in particular should be held culpable for the anti-Chinese hysteria of that time. By the 1870s, the country was experiencing a post-Civil War economic downturn. Jobs were hard to come by. In California, the gold that so many people had flooded in to find was already mostly gone by the early 1850s. Meanwhile, the monopolistic railway companies (and most other industries), exploited Chinese workers by paying them less than the going wage for white workers. Instead of directing their hatred solely at the Goliath-like industrial giants, white labor turned to a seemingly easier target. A couple quick examples:

Samuel Gompers, founder of the AFL, co-authored a paper entitled, "Some Reasons for Chinese Exclusion. Meat vs. Rice. American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism. Which Shall Survive?"

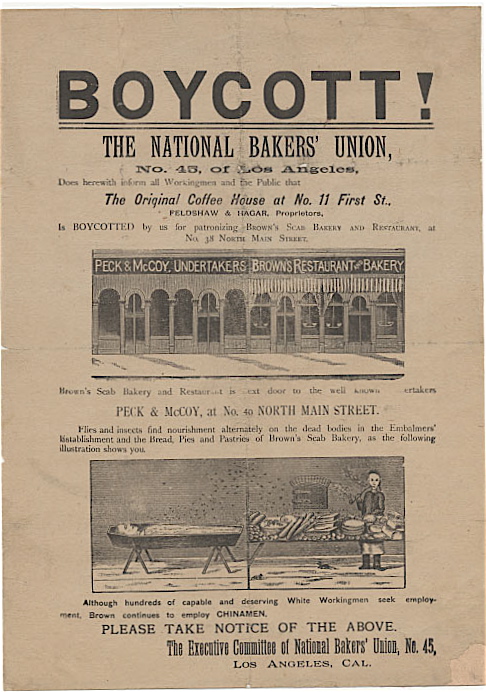

I'm not going to reproduce the most grossly offensive posters, pamphlets, and cartoons I've found that were produced by labor advocates in opposition to the Chinese, but here's a typically racist 1889 poster promoting a boycott of a business that was rumored to have hired Chinese workers: It's from the California Historical Society.

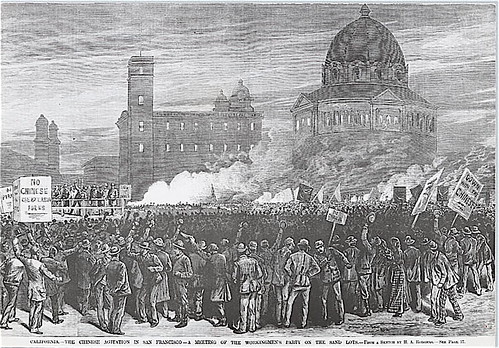

In San Francisco, anti-Chinese sentiment was common. The city's most famous anti-Chinese 'advocate' was Dennis Kearney publicly advocated rioting against both bosses and Chinese people at the old Sand Lot near City Hall.

White labor's anti-Chinese hysteria was horrifying, and it was also a missed opportunity. Directing rage towards immigrants (rather than business owners) didn't change labor conditions, or make workers wealthier. As usual, bigotry trumped solidarity.

Anti-Chinese violence peaked in the 1880s, but it's probably obvious that anti-Chinese sentiment (and legislation) wasn't over. It wasn't until WWII that there were significant improvements in legal and living conditions for Chinese people living here. And of course, racism directed at Chinese-American's is still a major issue. A 2001 phone study indicated that one in four Americans has 'strong negative feelings' towards Chinese Americans.

I'm going to close this out for now. Next week I should have some more on Chinese resistance to racism.

Signing off,

During the Gold Rush, prospectors, mostly men, flooded into San Francisco from all over the world. Most came from the Eastern United States, but also from outside of the country, especially Chile and China. Chinese gold-seekers made up a significant portion of the new 'settlers', setting up communities in San Francisco and in rural areas too.

This 1852 photo by J. B. Starkweather shows a rare site: Chinese and European Americans working together in a gold mining operation.

Over the next few decades, Chinese immigrants became involved in a wide-range of work: Rurally, Chinese settlers created the fishing industry here, established agriculture in the Central Valley, and worked as laborers building the levee systems on the Delta, almost always living in isolated, Chinese-only communities. By the 1860s, 2/3 of the laborers building the Western portion of the transcontinental railroad were Chinese men.

In urban settings, Chinese workers took jobs in just about every trade: manufacturing, building, and running small businesses including laundries, restaurants, markets, and repair shops. Around the Bay Area, traveling Chinese peddlers sold fresh produce out of large baskets that they'd carry from house to house, and later from the back of horse-drawn produce carts.

Like many immigrants, new arrivals from China tended to stick together in the same neighborhoods, seeking out and forming supportive associations with people who came from their same regions and extended families back home. But the segregation of Chinese men and women into Chinatowns wasn't just a preference of the residents there. It was mandated by law and required for safety.

It would be difficult to exaggerate the level of hostility and violence directed towards Chinese-Americans in the late 19th century. Before I started reading about this a few weeks ago, I had no idea how overwhelming and horrific this bit of history was: white Americans, encouraged by labor leaders and sometimes officially sanctioned by local governments, perpetrated a series of pogroms against Chinese communities throughout the late 1800s. A few examples:

- In 1871 in Los Angeles a brutal race riot left roughly 20 Chinese men dead, after white residents ransacked Chinatown there.

- In 1885, in Wyoming, European immigrant mine workers rioted against Chinese workers (who were paid less than white workers and who had historically been recruited as strikebreakers), killing 28 Chinese miners and destroying 75 of their homes.

- In 1886, virtually every Chinese resident of Seattle was rounded up in an attempt to remove them from the city.

- In 1887, 31 Chinese gold miners were murdered by bandits in Oregon, and no one was prosecuted for the murders.

"Massacre of the Chinese at Rock Springs, Wyoming" From Harper's Weekly housed at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Legal repression of Chinese immigrants escalated dramatically as the years progressed: By 1852, Chinese gold miners were subject to a significant foreigner tax that no other international miners were required to pay. Two years later, the Supreme Court of California extended to Chinese people a ban already in place prohibiting 'Negroes' and 'Indians' from testifying for or against white people. In 1872, Chinese people were barred from owning real estate or business licenses in California. And devastatingly, in 1882, Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring Chinese laborers from entering the country. This ban was generally applied to almost every Chinese person, making it impossible for example for Chinese men already living in the US to bring their families here to join them. (And because the immigrants who came here from China were almost exclusively male, and because the Exclusion Act prohibited anyone else from coming, the Chinese community dwindled as its bachelor class aged without raising children.) The Chinese Exclusion Act wasn't repealed until the 1940s and the severe immigration quotas reserved only for Chinese immigrants weren't ended until 1965. 1965!

Theorists and intellectuals fell over each other advocating for the removal of Chinese people from this country. Here's a fairly typical anti-Chinese screed of the time, devoted to the "Chinese Question". I confess, I didn't read this whole steaming pile of garbage, and instead skipped to the final chapter (starts on 196) titled "One course, and one course only, can stay the Eastward migration of the yellow race, and its gradual conquest of the land." You can guess what course that is. 'Progressive' non-Chinese thinkers tended to advocate for Chinese immigrants solely on the basis that they were willing to do the tedious, humiliating, or back-breaking work that white people were refusing to take. Hmm, sounds familiar.

Government leaders and others in the mainstream were certainly responsible for the legal sanction of racism here, but labor leaders in particular should be held culpable for the anti-Chinese hysteria of that time. By the 1870s, the country was experiencing a post-Civil War economic downturn. Jobs were hard to come by. In California, the gold that so many people had flooded in to find was already mostly gone by the early 1850s. Meanwhile, the monopolistic railway companies (and most other industries), exploited Chinese workers by paying them less than the going wage for white workers. Instead of directing their hatred solely at the Goliath-like industrial giants, white labor turned to a seemingly easier target. A couple quick examples:

Samuel Gompers, founder of the AFL, co-authored a paper entitled, "Some Reasons for Chinese Exclusion. Meat vs. Rice. American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism. Which Shall Survive?"

I'm not going to reproduce the most grossly offensive posters, pamphlets, and cartoons I've found that were produced by labor advocates in opposition to the Chinese, but here's a typically racist 1889 poster promoting a boycott of a business that was rumored to have hired Chinese workers: It's from the California Historical Society.

In San Francisco, anti-Chinese sentiment was common. The city's most famous anti-Chinese 'advocate' was Dennis Kearney publicly advocated rioting against both bosses and Chinese people at the old Sand Lot near City Hall.

White labor's anti-Chinese hysteria was horrifying, and it was also a missed opportunity. Directing rage towards immigrants (rather than business owners) didn't change labor conditions, or make workers wealthier. As usual, bigotry trumped solidarity.

Anti-Chinese violence peaked in the 1880s, but it's probably obvious that anti-Chinese sentiment (and legislation) wasn't over. It wasn't until WWII that there were significant improvements in legal and living conditions for Chinese people living here. And of course, racism directed at Chinese-American's is still a major issue. A 2001 phone study indicated that one in four Americans has 'strong negative feelings' towards Chinese Americans.

I'm going to close this out for now. Next week I should have some more on Chinese resistance to racism.

Signing off,

Labels:

1800s,

Asian American,

Chinese American,

gold rush,

labor,

racism

6.19.2007

Some self indulgence

My next topic – Chinese-American workers and the relationship of the white labor movement to the Chinese community of the Bay Area is kind of enormous. While I continue my 'research' (mostly late night googling), you can tide yourself over with documentation of my efforts.

Friday afternoon: our intrepid blogger sets off for a research mission.

Damn. Missed my train. Yet, in less time than it takes me to answer my emails, I made it to San Francisco. Near, and yet far from my provincial home in Oak Land. First attraction in SF, the F line.

It's designed for the enjoyment of history nerds like me! And of course to attract tourist dollars. But so what! It's so shiney!

Woo-hoo! Boat train!

OK, time to go to the library. Every time I come to the San Francisco Main branch I play "Where are the books?"

Nope, not here:

Not here either.

None here either. Oh well, who has time for books anyway - time is limited when you've got to think about childcare. I quickly move on to the hallowed grounds of the SF History Center! Here, you must check your bags, sign in at the front desk, and walk silently among the softly-lit shelves.

It's best to speak in hushed tones around the historians - they scare easily. And frankly, I was kind of sweaty and incoherent when I arrived. I cornered a soft-spoken librarian and described my blog project to him in detail. When I was finished he nodded helpfully and then said, "It would be easier if you put your request in the form of a question."

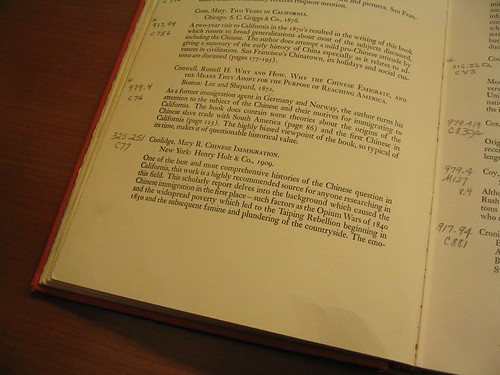

He was able to assist me though by piling a large stack of bibliographies in front of me. Since I've never done academic research of any kind, I'm not sure if that's the best place to start, but at least I now know what to look up when I go back.

I really hit pay dirt with this bibliography about Chinese American's in California. I love picturing the poor soul (or enthusiastic obsessive compulsive) who hand wrote the dewey decimal number for each entry into the margins.

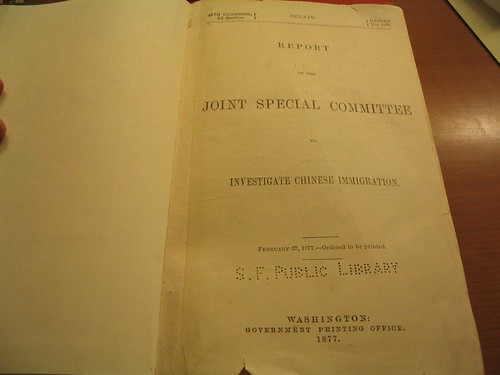

I spent most of the afternoon reading from this congressional report on Chinese Immigration – a nauseating foundation for the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

I found out later that the whole ugly thing is digitized. So if I can make it through hundreds of pages of the white men of business and congress falling over each other to present Chinese immigrants as gamblers, prostitutes, and disease vectors, I'll be able to complete it at my leisure.

Several hours later, my childcare was about to run out. I collected my backpack from the quiet librarian, and as I left, he mentioned that perhaps I should check the Chinese Center on the third floor. WTF?! I should have been there in the first place!

Still, I was in a good mood – a history junkie happily fixed – the whole way home. I even stopped to say hello to the folks painting a new mural on the Ella Baker Center. Good luck muralists! Way to represent for Oakland!

Friday afternoon: our intrepid blogger sets off for a research mission.

Damn. Missed my train. Yet, in less time than it takes me to answer my emails, I made it to San Francisco. Near, and yet far from my provincial home in Oak Land. First attraction in SF, the F line.

It's designed for the enjoyment of history nerds like me! And of course to attract tourist dollars. But so what! It's so shiney!

Woo-hoo! Boat train!

OK, time to go to the library. Every time I come to the San Francisco Main branch I play "Where are the books?"

Nope, not here:

Not here either.

None here either. Oh well, who has time for books anyway - time is limited when you've got to think about childcare. I quickly move on to the hallowed grounds of the SF History Center! Here, you must check your bags, sign in at the front desk, and walk silently among the softly-lit shelves.

It's best to speak in hushed tones around the historians - they scare easily. And frankly, I was kind of sweaty and incoherent when I arrived. I cornered a soft-spoken librarian and described my blog project to him in detail. When I was finished he nodded helpfully and then said, "It would be easier if you put your request in the form of a question."

He was able to assist me though by piling a large stack of bibliographies in front of me. Since I've never done academic research of any kind, I'm not sure if that's the best place to start, but at least I now know what to look up when I go back.

I really hit pay dirt with this bibliography about Chinese American's in California. I love picturing the poor soul (or enthusiastic obsessive compulsive) who hand wrote the dewey decimal number for each entry into the margins.

I spent most of the afternoon reading from this congressional report on Chinese Immigration – a nauseating foundation for the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

I found out later that the whole ugly thing is digitized. So if I can make it through hundreds of pages of the white men of business and congress falling over each other to present Chinese immigrants as gamblers, prostitutes, and disease vectors, I'll be able to complete it at my leisure.

Several hours later, my childcare was about to run out. I collected my backpack from the quiet librarian, and as I left, he mentioned that perhaps I should check the Chinese Center on the third floor. WTF?! I should have been there in the first place!

Still, I was in a good mood – a history junkie happily fixed – the whole way home. I even stopped to say hello to the folks painting a new mural on the Ella Baker Center. Good luck muralists! Way to represent for Oakland!

Labels:

1800s,

art,

Asian American,

Chinese American,

labor,

library,

me,

streetcar

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)