I told the kids I was taking them to the Rosie the Riveter Park, which they seemed very excited about it despite the fact they've never heard of Rosie the Riveter. The concept of Rosie the Riveter is confusing because the idea that there was a time when women weren't allowed to work the same jobs as men is foreign to them. I mean, their parents are lesbians – in their world, women do everything including fixing cars, washing dishes, and rolling children up in their blankets like human burritos; why shouldn't women rivet? And what the hell is a rivet anyway? On the way to the park I gave them my now classic lecture (most recently used when discussing Martin Luther King Jr.) about how

Sometimes People Have Ideas That Aren't True, and

It's Important to Tell Those People That ANYONE Can Be a Riveter (or that anyone should be able to ride in the front of the bus, depending on which lecture I'm giving). (I restrained myself from giving a lecture on war profiteering, which might have been more appropriate for this memorial – more on that in a minute.)

I hadn't been to Richmond in a while, and when I got off the freeway, I was completely confused by the impenetrable wall of condos.

This isn't the

Richmond I'm familiar with, and if it is part of Richmond now, what is the city doing with all the new property taxes? Please, someone with some real Richmond knowledge fill me in. In any case, I got lost in condo land and finally ended up at an upscale mini-mart where I asked the proprietor for directions to

Rosie the Riveter Park. He looked over his glasses at me and chuckled (I'm not exaggerating - he really chuckled!), "Your expectations are too high," and directed me back to a patch of grass next to a parking lot I'd just passed.

The kids and I got out at the Rosie Memorial, a little exhibit about women homefront workers that was commissioned by the City of Richmond, and designed by artist Susan Schwartzenberg (Susan, why don't you have a website?) and landscape architect

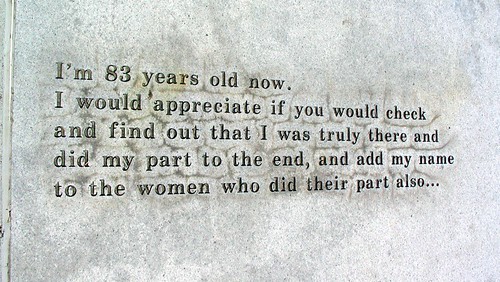

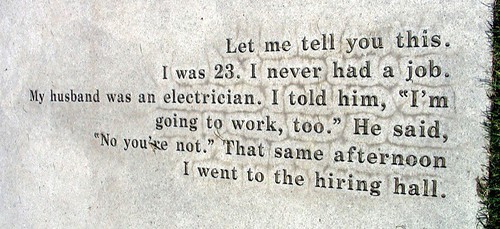

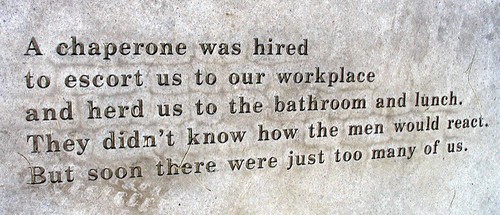

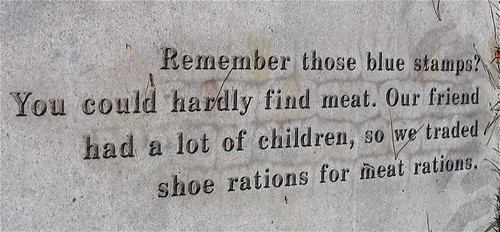

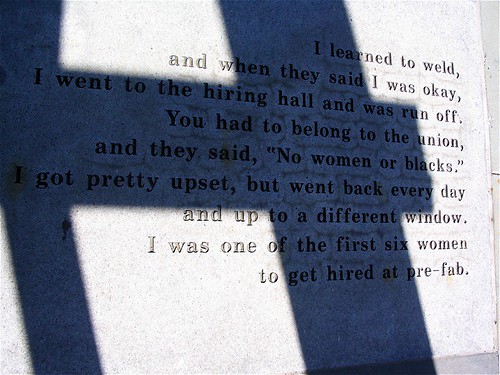

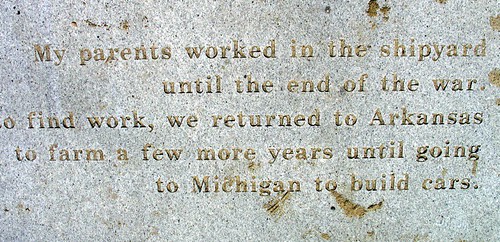

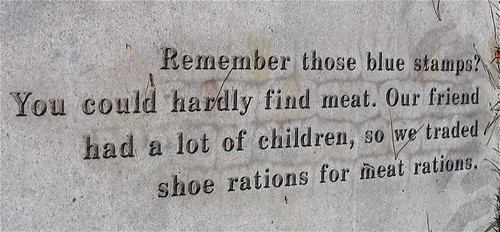

Cheryl Barton. Given, I'm a nerd, but I really liked it. The memorial runs the length of a Liberty Ship, and as you walk along the path spanning the ships distance, you can read a mini labor history of WWII, with a focus on people of color and women. Also interspersed are quotes from women shipyard workers, and these, along with photos posted at the site, are the most affecting part of the exhibit.

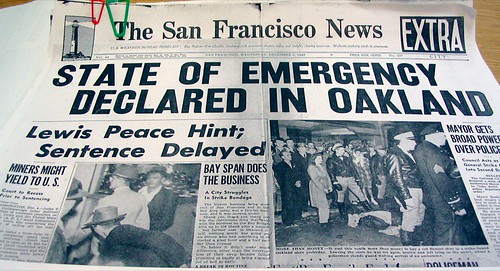

The memorial is planted on the former site of Kaiser Shipyard number 2, where steel magnate Henry J. Kaiser employed many thousands of workers to build ships for WWII.

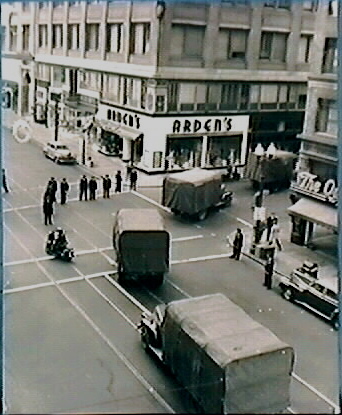

Richmond's history is inseparably linked with Kaiser's factories and with the war. Richmond became a largely African-American city (36% of the population according to the latest census) as a result of migration related to the war industries. And the poverty that many Richmond residents confront now is directly linked with the city's failure to create adequate housing and infrastructure for its many new residents during the war, and the sudden disappearance of jobs that occurred when the war was over.

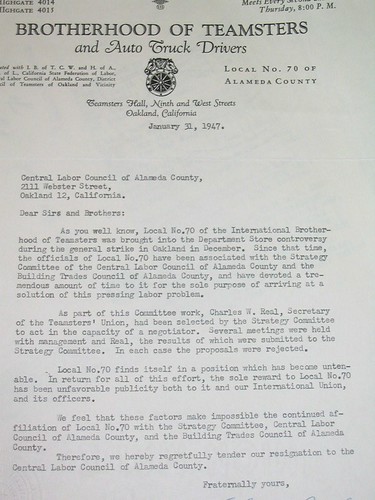

In 1940, Richmond had a small town feeling and a population of around 23,000. By 1950, the population was more than 99,000. Workers came in carloads and trainloads, brought by the more than 170 recruiters that Kaiser employed around the state and around the country to power the shipbuilding empire that he had centered in Richmond. So desperate was Kaiser for workers that at one point, LA recruiters instituted a "work for drunks" program where judges issued suspended sentences to 'vagrants' in exchange for an agreement to come work in the Richmond yards. That program didn't last long, but even for the average newly arrived worker, (if you can say that there was an 'average' since folks came from all over the state, from all regions of the country, and represented dozens of ethnic groups) the attrition rate was high. Once workers arrived they found limited housing, working conditions that were both stressful and tedious, and the loneliness of leaving home. The many new African-American workers transplanted from the South found themselves subject to the same Jim Crow racist hiring and housing practices they were familiar with from back home. War industry work crews were racially segregated, Black workers were rarely promoted to supervisory positions, and Black workers were refused membership in the major unions and instead relegated to auxiliary 'negro' unions where members were expected to pay dues but received little or no protection. (White women faced job discrimination as well, receiving significantly lower pay for jobs that white male workers got more for). While many protested these conditions, for example, in the Sausalito shipyards nearly all the Black employees walked out in protest of racist conditions in 1943, government agencies, white labor leaders, and industrialist business-owners were less than sympathetic. Outside of the factory, public housing built during the war was segregated in Richmond, as it was in Oakland and elsewhere in the Bay Area. (According to

The Second Gold Rush, details on that book below, Berkeley community leader Byron Rumford started a petition drive protesting public housing segregation which finally lead to federally mandated integration of Berkeley/Albany public housing in 1946.) Basic workplace rights and decent housing were a struggle for Richmond's many new Black residents. For their part, newly arrived white Southern workers tended to complain about 'having to' work side-by-side with African-Americans.

Who was

Henry J. Kaiser? He was your basic guy-out-to-make-a-buck, all-American, success story. He got his big start running a road-paving business, and ended his life turning

Honolulu into the tourist sink that it is today. He was successful to say the least – his company, along with another Bay Area local,

Bechtel and four other companies managed the construction of the Hoover Dam. During the war, Kaiser employees in Richmond (and his three other factories along the West Coast) were building a whole war ship in about a month (the record was set when workers constructed an entire ship in just over four days). His name also lives on in the Kaiser Permanente HMO, which was

created because Kaiser needed to provide some basic health services to his thousands of employees, and who can afford that kind of expense (while maintaining a millionaire lifestyle)?

When the war ended, Kaiser moved on to new projects. He even (briefly) got into the

auto industry. For the thousands of factory workers who had moved to the Bay Area, many full of patriotism and hope for the future, life wasn't quite as easy as Kaiser's. The jobs disappeared almost immediately. Soldiers came home and were given priority for the few jobs that remained. Women and men of color found themselves fired or demoted to make way for white men who were prioritized by employers. Today Richmond is still full of

art,

culture, and

hard work, but undeniably, Richmond has been scarred by the poverty that is a legacy of the war industry here. The Rosie Memorial is just a little thing, but I loved getting to learn more about why things happened the way they did here. I was glad to come. I confess that the kids liked the nearby boats a lot more than that exhibit, but what can they do, they're a captive audience.

This entry barely scratches the surface of what can be said about the long-term impact of WWII industry on race, gender, and economics here. If you want to learn more, there are a bunch of other sources I'd recommend:

Marilynn S. Johnson's

The Second Gold Rush provided a bunch of references for this post. It's factually dense but it maintains a readable narrative. I don't think you have to be as obsessive as I am to enjoy it, which is unusual for this kind of regional history book.

Fight or Be Slaves also has tons of information about this period.

Robert Self discusses issues related to changing racial dynamics in the East Bay after WWII in

American Babylon. Unfortunately, I got about 50 pages into this book last summer, and then accidentally left it at

Feather River Family Camp, so I can't tell you for sure if it's worth reading, but my friend Jess was just saying good things about it, so on his recommendation, I'll say, go for it.

I thought this

Bay Crossings article had some interesting history about water travel related to Richmond.

Finally, I was inspired to check out the Rosie park after reading a nice article about it in the

San Francisco Bayview.

The article originally appeared on Black Commentator, but I'm including the Bayview link because of some additional notes at the end of their version.Hey, if you want to learn more,

Here's a whole pile of relevant sources.

I'll send you out with this video by historian Betty Soskin on African-Americans in the Richmond war industries.

You can read some details about the content of the video here.