6.26.2007

S.F. Shootout

I'm glad that I'm not a professional historian because if I were, I might have to find some other way to express this: Dennis Kearney* was an utter ass-wipe. An immigrant himself, Kearney founded California's briefly influential (and highly racist) Workingman's Party. He made a political career out of the thoughtful slogan, "The Chinese Must Go". His fiery speeches were quite radical – he advocated lynching of wealthy business owners – but he wasn't marginal. His political ally, Isaac Kalloch, became San Francisco's mayor in 1879.

That is disturbing, but not surprising. Here's the crazy part: in the 1870s, the founder and editor of the Chronicle, Charles de Young, railed against Kearney and Kalloch (then only a mayoral candidate) in his paper. I haven't read the editorials directly – anyone know of where I can find those archives online? But from what I understand, de Young wasn't particularly concerned with Kalloch's racism, but more with his popularity. Trying to undermine the mayoral candidate, he publicly exposed a sex scandal that Kalloch (a Baptist minister) had been involved with in another state. Kalloch ridiculed de Young right back and from the pulpit, calling de Young's mother "whore-mongering", and then in retaliation de Young, the editor of the Chronicle, shot Kalloch, the mayoral candidate!

Kalloch survived, and won the election in part because of the sympathy he garnered for his injury, but a year later his son, defending the family honor, fatally shot de Young. He admitted to the shooting but got off free. Fortunately, Kearney's Workingman's Party faded shortly thereafter, but Kalloch did fine, serving two years as mayor.

*Note that Wikipedia reveals that Kearny Street, which runs right through Chinatown in SF is not actually named after Dennis Kearney. This information comes as a relief, but I wasn't too excited to learn who it was named after: Stephen Kearny, who founded of the US Cavalry and used those troops to expand white US occupation into Native American homelands in the Western part of the continent. He went on to command a number of battalions in the Mexican-American War, winning California for the US of A, which, I imagine, is why he got a street named after him in San Francisco. Related: we can also breathe a sigh of relief that Geary street is named after a former postmaster, not California Congressman Thomas Geary, who wrote an 1892 law extending the Chinese Exclusion Act, and expanding it to require Chinese-Americans to carry permits at all times, or risk deportation or punishment by hard labor. His act also denied habeus corpus to imprisoned Chinese-Americans, removing their rights to ask a judge to review the legality of their detentions. If you want to know who any other SF streets are not named for, look at this site.

Labels:

1800s,

Asian American,

Chinese American,

labor,

newspapers,

racism,

SF

6.25.2007

Anti-Chinese violence

I’m going to do a few entries about the history Chinese-Americans in the Bay Area, and the relationship between the white labor movement and Chinese workers. It's been pretty disturbing reading about this stuff. I had a sense of some of the racism that was historically directed at Chinese immigrants, but I certainly didn't understand the scale. The most appropriate word to describe what happened to Chinese people here is probably 'pogroms'. I grew up here in California, and I definitely didn't learn about any of this in school. Anyway, here's the first post – about labor:

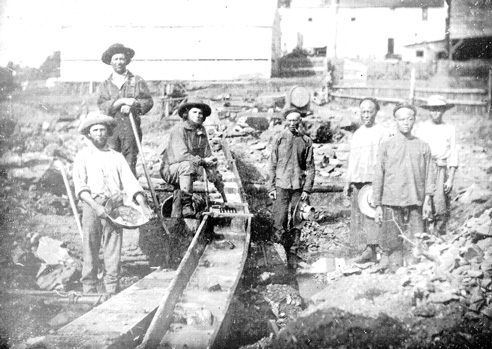

During the Gold Rush, prospectors, mostly men, flooded into San Francisco from all over the world. Most came from the Eastern United States, but also from outside of the country, especially Chile and China. Chinese gold-seekers made up a significant portion of the new 'settlers', setting up communities in San Francisco and in rural areas too.

This 1852 photo by J. B. Starkweather shows a rare site: Chinese and European Americans working together in a gold mining operation.

Over the next few decades, Chinese immigrants became involved in a wide-range of work: Rurally, Chinese settlers created the fishing industry here, established agriculture in the Central Valley, and worked as laborers building the levee systems on the Delta, almost always living in isolated, Chinese-only communities. By the 1860s, 2/3 of the laborers building the Western portion of the transcontinental railroad were Chinese men.

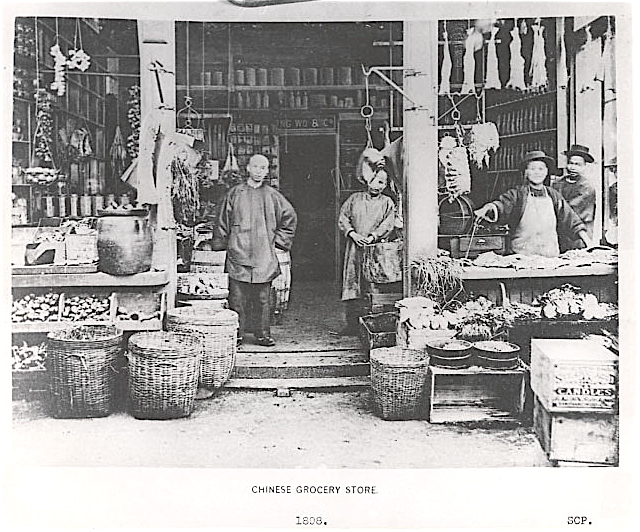

In urban settings, Chinese workers took jobs in just about every trade: manufacturing, building, and running small businesses including laundries, restaurants, markets, and repair shops. Around the Bay Area, traveling Chinese peddlers sold fresh produce out of large baskets that they'd carry from house to house, and later from the back of horse-drawn produce carts.

Like many immigrants, new arrivals from China tended to stick together in the same neighborhoods, seeking out and forming supportive associations with people who came from their same regions and extended families back home. But the segregation of Chinese men and women into Chinatowns wasn't just a preference of the residents there. It was mandated by law and required for safety.

It would be difficult to exaggerate the level of hostility and violence directed towards Chinese-Americans in the late 19th century. Before I started reading about this a few weeks ago, I had no idea how overwhelming and horrific this bit of history was: white Americans, encouraged by labor leaders and sometimes officially sanctioned by local governments, perpetrated a series of pogroms against Chinese communities throughout the late 1800s. A few examples:

- In 1871 in Los Angeles a brutal race riot left roughly 20 Chinese men dead, after white residents ransacked Chinatown there.

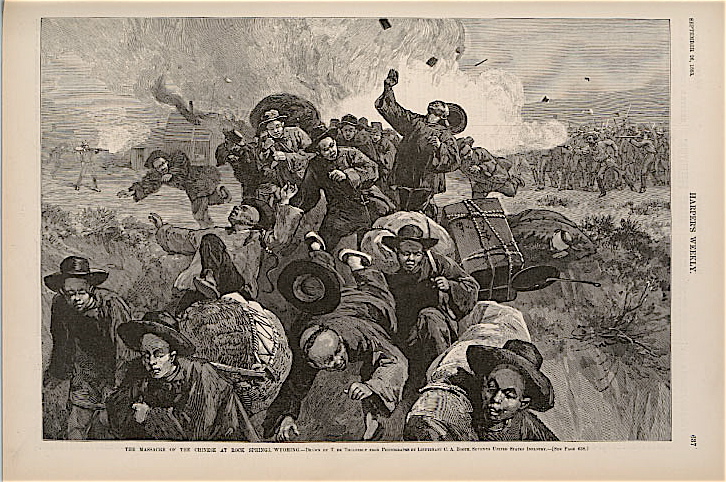

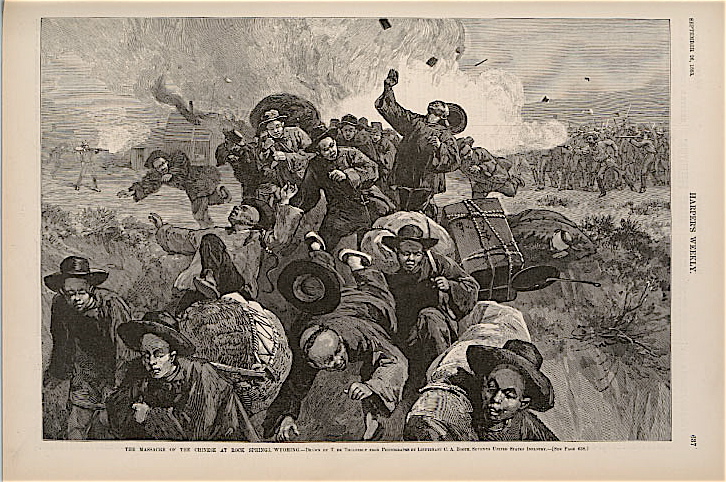

- In 1885, in Wyoming, European immigrant mine workers rioted against Chinese workers (who were paid less than white workers and who had historically been recruited as strikebreakers), killing 28 Chinese miners and destroying 75 of their homes.

- In 1886, virtually every Chinese resident of Seattle was rounded up in an attempt to remove them from the city.

- In 1887, 31 Chinese gold miners were murdered by bandits in Oregon, and no one was prosecuted for the murders.

"Massacre of the Chinese at Rock Springs, Wyoming" From Harper's Weekly housed at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Legal repression of Chinese immigrants escalated dramatically as the years progressed: By 1852, Chinese gold miners were subject to a significant foreigner tax that no other international miners were required to pay. Two years later, the Supreme Court of California extended to Chinese people a ban already in place prohibiting 'Negroes' and 'Indians' from testifying for or against white people. In 1872, Chinese people were barred from owning real estate or business licenses in California. And devastatingly, in 1882, Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring Chinese laborers from entering the country. This ban was generally applied to almost every Chinese person, making it impossible for example for Chinese men already living in the US to bring their families here to join them. (And because the immigrants who came here from China were almost exclusively male, and because the Exclusion Act prohibited anyone else from coming, the Chinese community dwindled as its bachelor class aged without raising children.) The Chinese Exclusion Act wasn't repealed until the 1940s and the severe immigration quotas reserved only for Chinese immigrants weren't ended until 1965. 1965!

Theorists and intellectuals fell over each other advocating for the removal of Chinese people from this country. Here's a fairly typical anti-Chinese screed of the time, devoted to the "Chinese Question". I confess, I didn't read this whole steaming pile of garbage, and instead skipped to the final chapter (starts on 196) titled "One course, and one course only, can stay the Eastward migration of the yellow race, and its gradual conquest of the land." You can guess what course that is. 'Progressive' non-Chinese thinkers tended to advocate for Chinese immigrants solely on the basis that they were willing to do the tedious, humiliating, or back-breaking work that white people were refusing to take. Hmm, sounds familiar.

Government leaders and others in the mainstream were certainly responsible for the legal sanction of racism here, but labor leaders in particular should be held culpable for the anti-Chinese hysteria of that time. By the 1870s, the country was experiencing a post-Civil War economic downturn. Jobs were hard to come by. In California, the gold that so many people had flooded in to find was already mostly gone by the early 1850s. Meanwhile, the monopolistic railway companies (and most other industries), exploited Chinese workers by paying them less than the going wage for white workers. Instead of directing their hatred solely at the Goliath-like industrial giants, white labor turned to a seemingly easier target. A couple quick examples:

Samuel Gompers, founder of the AFL, co-authored a paper entitled, "Some Reasons for Chinese Exclusion. Meat vs. Rice. American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism. Which Shall Survive?"

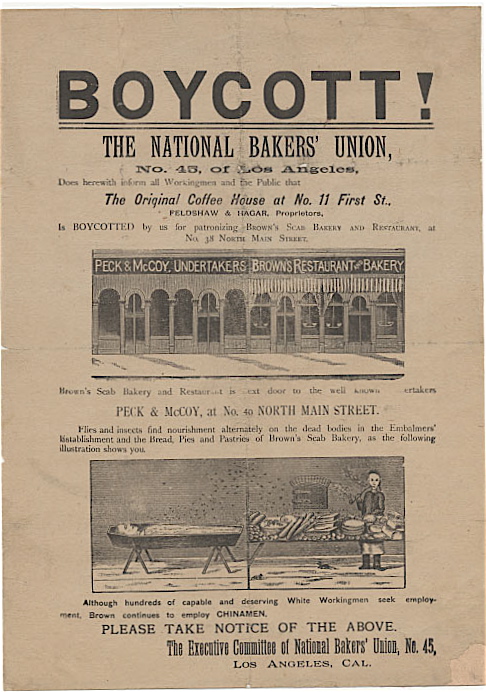

I'm not going to reproduce the most grossly offensive posters, pamphlets, and cartoons I've found that were produced by labor advocates in opposition to the Chinese, but here's a typically racist 1889 poster promoting a boycott of a business that was rumored to have hired Chinese workers: It's from the California Historical Society.

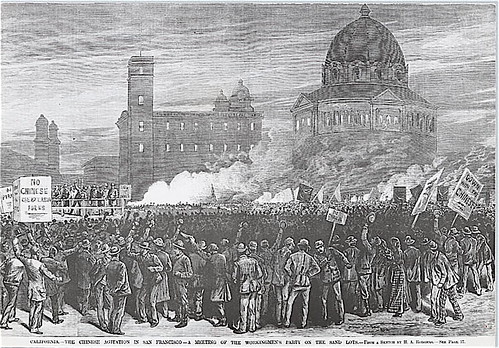

In San Francisco, anti-Chinese sentiment was common. The city's most famous anti-Chinese 'advocate' was Dennis Kearney publicly advocated rioting against both bosses and Chinese people at the old Sand Lot near City Hall.

White labor's anti-Chinese hysteria was horrifying, and it was also a missed opportunity. Directing rage towards immigrants (rather than business owners) didn't change labor conditions, or make workers wealthier. As usual, bigotry trumped solidarity.

Anti-Chinese violence peaked in the 1880s, but it's probably obvious that anti-Chinese sentiment (and legislation) wasn't over. It wasn't until WWII that there were significant improvements in legal and living conditions for Chinese people living here. And of course, racism directed at Chinese-American's is still a major issue. A 2001 phone study indicated that one in four Americans has 'strong negative feelings' towards Chinese Americans.

I'm going to close this out for now. Next week I should have some more on Chinese resistance to racism.

Signing off,

During the Gold Rush, prospectors, mostly men, flooded into San Francisco from all over the world. Most came from the Eastern United States, but also from outside of the country, especially Chile and China. Chinese gold-seekers made up a significant portion of the new 'settlers', setting up communities in San Francisco and in rural areas too.

This 1852 photo by J. B. Starkweather shows a rare site: Chinese and European Americans working together in a gold mining operation.

Over the next few decades, Chinese immigrants became involved in a wide-range of work: Rurally, Chinese settlers created the fishing industry here, established agriculture in the Central Valley, and worked as laborers building the levee systems on the Delta, almost always living in isolated, Chinese-only communities. By the 1860s, 2/3 of the laborers building the Western portion of the transcontinental railroad were Chinese men.

In urban settings, Chinese workers took jobs in just about every trade: manufacturing, building, and running small businesses including laundries, restaurants, markets, and repair shops. Around the Bay Area, traveling Chinese peddlers sold fresh produce out of large baskets that they'd carry from house to house, and later from the back of horse-drawn produce carts.

Like many immigrants, new arrivals from China tended to stick together in the same neighborhoods, seeking out and forming supportive associations with people who came from their same regions and extended families back home. But the segregation of Chinese men and women into Chinatowns wasn't just a preference of the residents there. It was mandated by law and required for safety.

It would be difficult to exaggerate the level of hostility and violence directed towards Chinese-Americans in the late 19th century. Before I started reading about this a few weeks ago, I had no idea how overwhelming and horrific this bit of history was: white Americans, encouraged by labor leaders and sometimes officially sanctioned by local governments, perpetrated a series of pogroms against Chinese communities throughout the late 1800s. A few examples:

- In 1871 in Los Angeles a brutal race riot left roughly 20 Chinese men dead, after white residents ransacked Chinatown there.

- In 1885, in Wyoming, European immigrant mine workers rioted against Chinese workers (who were paid less than white workers and who had historically been recruited as strikebreakers), killing 28 Chinese miners and destroying 75 of their homes.

- In 1886, virtually every Chinese resident of Seattle was rounded up in an attempt to remove them from the city.

- In 1887, 31 Chinese gold miners were murdered by bandits in Oregon, and no one was prosecuted for the murders.

"Massacre of the Chinese at Rock Springs, Wyoming" From Harper's Weekly housed at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Legal repression of Chinese immigrants escalated dramatically as the years progressed: By 1852, Chinese gold miners were subject to a significant foreigner tax that no other international miners were required to pay. Two years later, the Supreme Court of California extended to Chinese people a ban already in place prohibiting 'Negroes' and 'Indians' from testifying for or against white people. In 1872, Chinese people were barred from owning real estate or business licenses in California. And devastatingly, in 1882, Congress enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring Chinese laborers from entering the country. This ban was generally applied to almost every Chinese person, making it impossible for example for Chinese men already living in the US to bring their families here to join them. (And because the immigrants who came here from China were almost exclusively male, and because the Exclusion Act prohibited anyone else from coming, the Chinese community dwindled as its bachelor class aged without raising children.) The Chinese Exclusion Act wasn't repealed until the 1940s and the severe immigration quotas reserved only for Chinese immigrants weren't ended until 1965. 1965!

Theorists and intellectuals fell over each other advocating for the removal of Chinese people from this country. Here's a fairly typical anti-Chinese screed of the time, devoted to the "Chinese Question". I confess, I didn't read this whole steaming pile of garbage, and instead skipped to the final chapter (starts on 196) titled "One course, and one course only, can stay the Eastward migration of the yellow race, and its gradual conquest of the land." You can guess what course that is. 'Progressive' non-Chinese thinkers tended to advocate for Chinese immigrants solely on the basis that they were willing to do the tedious, humiliating, or back-breaking work that white people were refusing to take. Hmm, sounds familiar.

Government leaders and others in the mainstream were certainly responsible for the legal sanction of racism here, but labor leaders in particular should be held culpable for the anti-Chinese hysteria of that time. By the 1870s, the country was experiencing a post-Civil War economic downturn. Jobs were hard to come by. In California, the gold that so many people had flooded in to find was already mostly gone by the early 1850s. Meanwhile, the monopolistic railway companies (and most other industries), exploited Chinese workers by paying them less than the going wage for white workers. Instead of directing their hatred solely at the Goliath-like industrial giants, white labor turned to a seemingly easier target. A couple quick examples:

Samuel Gompers, founder of the AFL, co-authored a paper entitled, "Some Reasons for Chinese Exclusion. Meat vs. Rice. American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism. Which Shall Survive?"

I'm not going to reproduce the most grossly offensive posters, pamphlets, and cartoons I've found that were produced by labor advocates in opposition to the Chinese, but here's a typically racist 1889 poster promoting a boycott of a business that was rumored to have hired Chinese workers: It's from the California Historical Society.

In San Francisco, anti-Chinese sentiment was common. The city's most famous anti-Chinese 'advocate' was Dennis Kearney publicly advocated rioting against both bosses and Chinese people at the old Sand Lot near City Hall.

White labor's anti-Chinese hysteria was horrifying, and it was also a missed opportunity. Directing rage towards immigrants (rather than business owners) didn't change labor conditions, or make workers wealthier. As usual, bigotry trumped solidarity.

Anti-Chinese violence peaked in the 1880s, but it's probably obvious that anti-Chinese sentiment (and legislation) wasn't over. It wasn't until WWII that there were significant improvements in legal and living conditions for Chinese people living here. And of course, racism directed at Chinese-American's is still a major issue. A 2001 phone study indicated that one in four Americans has 'strong negative feelings' towards Chinese Americans.

I'm going to close this out for now. Next week I should have some more on Chinese resistance to racism.

Signing off,

Labels:

1800s,

Asian American,

Chinese American,

gold rush,

labor,

racism

6.19.2007

Some self indulgence

My next topic – Chinese-American workers and the relationship of the white labor movement to the Chinese community of the Bay Area is kind of enormous. While I continue my 'research' (mostly late night googling), you can tide yourself over with documentation of my efforts.

Friday afternoon: our intrepid blogger sets off for a research mission.

Damn. Missed my train. Yet, in less time than it takes me to answer my emails, I made it to San Francisco. Near, and yet far from my provincial home in Oak Land. First attraction in SF, the F line.

It's designed for the enjoyment of history nerds like me! And of course to attract tourist dollars. But so what! It's so shiney!

Woo-hoo! Boat train!

OK, time to go to the library. Every time I come to the San Francisco Main branch I play "Where are the books?"

Nope, not here:

Not here either.

None here either. Oh well, who has time for books anyway - time is limited when you've got to think about childcare. I quickly move on to the hallowed grounds of the SF History Center! Here, you must check your bags, sign in at the front desk, and walk silently among the softly-lit shelves.

It's best to speak in hushed tones around the historians - they scare easily. And frankly, I was kind of sweaty and incoherent when I arrived. I cornered a soft-spoken librarian and described my blog project to him in detail. When I was finished he nodded helpfully and then said, "It would be easier if you put your request in the form of a question."

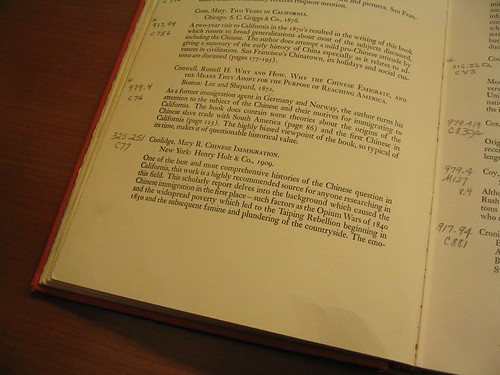

He was able to assist me though by piling a large stack of bibliographies in front of me. Since I've never done academic research of any kind, I'm not sure if that's the best place to start, but at least I now know what to look up when I go back.

I really hit pay dirt with this bibliography about Chinese American's in California. I love picturing the poor soul (or enthusiastic obsessive compulsive) who hand wrote the dewey decimal number for each entry into the margins.

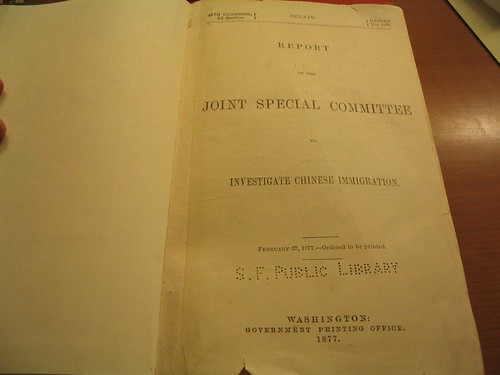

I spent most of the afternoon reading from this congressional report on Chinese Immigration – a nauseating foundation for the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

I found out later that the whole ugly thing is digitized. So if I can make it through hundreds of pages of the white men of business and congress falling over each other to present Chinese immigrants as gamblers, prostitutes, and disease vectors, I'll be able to complete it at my leisure.

Several hours later, my childcare was about to run out. I collected my backpack from the quiet librarian, and as I left, he mentioned that perhaps I should check the Chinese Center on the third floor. WTF?! I should have been there in the first place!

Still, I was in a good mood – a history junkie happily fixed – the whole way home. I even stopped to say hello to the folks painting a new mural on the Ella Baker Center. Good luck muralists! Way to represent for Oakland!

Friday afternoon: our intrepid blogger sets off for a research mission.

Damn. Missed my train. Yet, in less time than it takes me to answer my emails, I made it to San Francisco. Near, and yet far from my provincial home in Oak Land. First attraction in SF, the F line.

It's designed for the enjoyment of history nerds like me! And of course to attract tourist dollars. But so what! It's so shiney!

Woo-hoo! Boat train!

OK, time to go to the library. Every time I come to the San Francisco Main branch I play "Where are the books?"

Nope, not here:

Not here either.

None here either. Oh well, who has time for books anyway - time is limited when you've got to think about childcare. I quickly move on to the hallowed grounds of the SF History Center! Here, you must check your bags, sign in at the front desk, and walk silently among the softly-lit shelves.

It's best to speak in hushed tones around the historians - they scare easily. And frankly, I was kind of sweaty and incoherent when I arrived. I cornered a soft-spoken librarian and described my blog project to him in detail. When I was finished he nodded helpfully and then said, "It would be easier if you put your request in the form of a question."

He was able to assist me though by piling a large stack of bibliographies in front of me. Since I've never done academic research of any kind, I'm not sure if that's the best place to start, but at least I now know what to look up when I go back.

I really hit pay dirt with this bibliography about Chinese American's in California. I love picturing the poor soul (or enthusiastic obsessive compulsive) who hand wrote the dewey decimal number for each entry into the margins.

I spent most of the afternoon reading from this congressional report on Chinese Immigration – a nauseating foundation for the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

I found out later that the whole ugly thing is digitized. So if I can make it through hundreds of pages of the white men of business and congress falling over each other to present Chinese immigrants as gamblers, prostitutes, and disease vectors, I'll be able to complete it at my leisure.

Several hours later, my childcare was about to run out. I collected my backpack from the quiet librarian, and as I left, he mentioned that perhaps I should check the Chinese Center on the third floor. WTF?! I should have been there in the first place!

Still, I was in a good mood – a history junkie happily fixed – the whole way home. I even stopped to say hello to the folks painting a new mural on the Ella Baker Center. Good luck muralists! Way to represent for Oakland!

Labels:

1800s,

art,

Asian American,

Chinese American,

labor,

library,

me,

streetcar

6.17.2007

GLBT Historical Archives

I'm working on an entry about the history of SF and Oakland Chinatowns, but in the meantime, let me turn your attention to the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transexual Historical Society's page on youtube. This is the greatest use of youtube I can possibly imagine.

The first video I found there, theoretically of Black Sabbath playing the Folsom Street Parade in 1970, has been vexing me for a while. When I first discovered it, everyone I knew said "there's no fucking way that's Ozzy". I'm no expert on Oz, but I was also confused by the "Folsom Street Parade" thing. Folsom Street Fair didn't start until 1984. What was this drag parade doing South of Market with a big float advertising Sabbath?

Well, thanks to the rocker/investigators of youtube, I finally have my answer. According to user Terrible1, that dude in black atop the Sabbath float is noted San Francisco Satanist, Anton LeVay. Apparently, Ozzy himself also makes a brief appearance. Oz fans, feel free to let me know if you see him here.

Moving on to gayer historical matters, here's Sylvester tearing it up in 1985:

Cakalingus at 5:05.

Seriously, there's a lot of great stuff to explore on their page. This footage of the 1989 Castro sweep is probably only interesting to those of you who were there, but I always enjoy watching queers scream at riot cops. Listen for that catchy slogan: "Media is Bullshit! It's all a pack of LIES!"

I'll finish this post off with an extremely special video of the 1975 Mr. and Miss Gay San Francisco contest. I kind of like that there's no sound, it adds to the ethereal, Antediluvian quality.

The first video I found there, theoretically of Black Sabbath playing the Folsom Street Parade in 1970, has been vexing me for a while. When I first discovered it, everyone I knew said "there's no fucking way that's Ozzy". I'm no expert on Oz, but I was also confused by the "Folsom Street Parade" thing. Folsom Street Fair didn't start until 1984. What was this drag parade doing South of Market with a big float advertising Sabbath?

Well, thanks to the rocker/investigators of youtube, I finally have my answer. According to user Terrible1, that dude in black atop the Sabbath float is noted San Francisco Satanist, Anton LeVay. Apparently, Ozzy himself also makes a brief appearance. Oz fans, feel free to let me know if you see him here.

Moving on to gayer historical matters, here's Sylvester tearing it up in 1985:

Cakalingus at 5:05.

Seriously, there's a lot of great stuff to explore on their page. This footage of the 1989 Castro sweep is probably only interesting to those of you who were there, but I always enjoy watching queers scream at riot cops. Listen for that catchy slogan: "Media is Bullshit! It's all a pack of LIES!"

I'll finish this post off with an extremely special video of the 1975 Mr. and Miss Gay San Francisco contest. I kind of like that there's no sound, it adds to the ethereal, Antediluvian quality.

6.13.2007

South African strike

Speaking of general strikes, South African public sector workers are all out this week, with support from some private sector unions as well.

More at the Mail and Guardian and the BBC

More at the Mail and Guardian and the BBC

6.12.2007

Oakland General Strike Part II

Read Part I

Striking department store clerks, photo from the Oakland Museum of California.

In the first few days of December 1946, retail workers at Hastings' and Kahn's department stores, across the street from each other where Broadway meets Telegraph, had been on strike for more than a month. Most of the workers were women. Their pay was shitty, less than $16 a week, and worse, they were subjected to an absurd procedure where they had to show up to work first thing in the morning, and then wait in the basement (unpaid), until they were called to the floor to work. A clerk could easily be stuck in the basement all morning, or even all day.

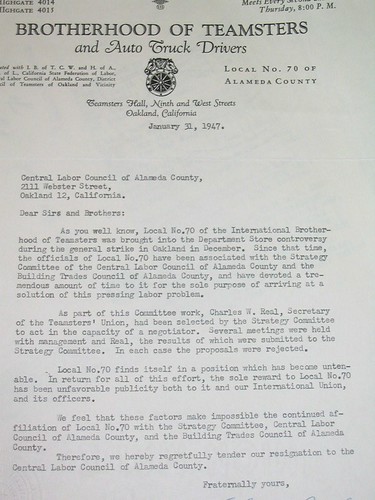

The Teamsters local had supported the retail workers strike from the beginning. They refused to deliver anything to the struck stores. (When I was at the Labor Archives, I even saw minutes from the Teamsters Local 70 meeting showing a member being expelled for trying to deliver to Kahn's in November.) The local NAACP and National Negro Congress publicly supported the striking workers. And union laborers had stopped painting and construction of a new elevator at Kahn's in solidarity.

On the business side, the Oakland Tribune, then run by republican powerhouse Joe Knowland, advocated a citywide ban of pickets. According to Albert Lannon's Fight or Be Slaves, right-wing city council members were publicly objecting to the use of the word 'scab'. Most detrimentally, the city agreed to send out the police force to escort delivery trucks to the stores, so they could keep stock for the Christmas shopping season.

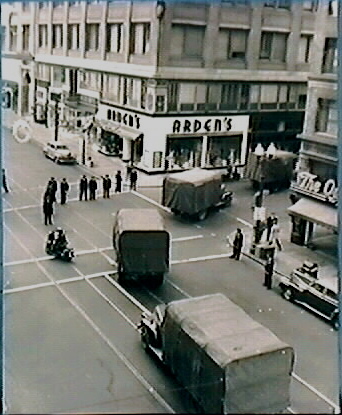

OPD escorting delivery trucks from the notoriously anti-union company G.I. Trucking. From the Oakland Museum of California.

That move was too much for the local labor council. The night of December 1st, a Saturday, Teamsters patrolled every roadway into Oakland to keep the delivery trucks away, and the labor council organized members to use their cars to block the parking spaces surrounding the effected stores. Several hundred picketers came out in the middle of the night to keep the scabs out.

Cops block the street to keep strikers out. From the Oakland Museum of California

At 4 in the morning the cops started towing the strikers cars and blocking off sections of Broadway, Telegraph, and San Pablo. When they waved the streetcars through their police line at 6:30 Sunday morning, a driver told the cops that he'd never crossed a picket line, got out of the car and removed its control box, causing an immovable backup along the streetcar line. The general strike was on, although it was another day before the whole city was out.

Tribune clipping from the Oakland History Room.

At a long and fevered meeting of various local AFL union leaders Sunday afternoon (the clerks were affiliated with the AFL), Teamsters pledged that because of the strikebreaking deliveries, they would shut down work in the East Bay starting Monday. Every other union but the milk truck drivers' agreed, and the milk truck drivers only insisted on working in order to get milk to local hospitals. Labor leaders went on the radio to declare Monday a 'work holiday' and to call everyone downtown, to the center of the strike, to show their support.

From the Oakland Museum of California.

At the peak, as many as 30,000 people were packed into the rainy downtown streets. The mood was excited to say the least. Bars were allowed to stay open, but they were only allowed to serve beer, and were told to turn their jukeboxes out to face the street, where people were literally dancing. All AFL building trades were shut down. All East Bay newspapers were shut down. Buses, streetcars, greyhounds, taxis, and trucking were stopped. Gas stations were closed too. Hotels, movie theaters, and larger restaurants and grocery stores were shut.

The picture's pretty blurry, but can you make out those huge grins? From the Oakland Museum again.

I've read conflicting stories on this, but from what I understand, the CIO, the second-largest umbrella union organization in Oakland, had offered their support the night before the strike. They were patently turned down. AFL leaders didn't want to be associated with the CIO whose on-the-ground organizers were largely communist. Robert Ash, the head of the labor council was quite progressive, but balked at working together, imagining headlines in the paper saying "Reds cause Anarchy Downtown" and so forth. Besides the communist associations, the AFL and CIO were rivals not comrades. Working directly with the CIO would have brought about ugly repercussions from national AFL leadership. The CIO honored picket lines anyway, and finally, on the third day of the strike, called for a general meeting to vote on whether to walk out themselves. A CIO walkout would have cut off gas and electricity to most of the city. At this suggestion, Oakland's city manager was ready to settle.

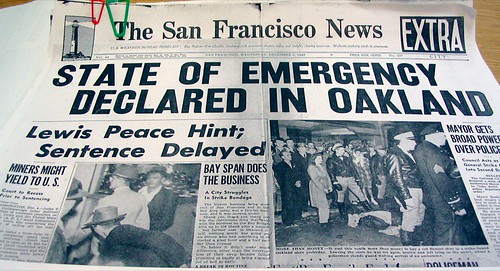

But the unions had lost the upper hand. The national vice president of the Teamsters, Dave Beck, told the local to withdraw from the general strike. He didn't support revolution, and apparently, the strike was developing that flavor. Rumors circulated that Governor Earl Warren was going to send in the National Guard, and the mayor had declared a state of emergency.

Instead of holding their ground, the union negotiated with Oakland's city manager only for an agreement that police would not be used to break strikes. There was no settlement for the department store clerks (who stayed on strike for eight more months, and then had to settle for a weak contract before they finally negotiated a better deal and a closed union shop in May of '47). There was certainly no attempt to make structural change in the city. Robert Ash from the Labor Council admitted later, in retrospect, that had they held out, they could have had more. Maybe they could have gotten the whole right-wing city leadership to resign.

But even that laudable goal suffers from a failure of imagination. Workers owned the city for those three days. They could have done anything. On the other hand, what can you do when you suddenly control your own world? When you have the power to rearrange everything, if only you can agree with tens of thousands of others who share that power? Who knew what to do with complete worker control of a city?

A year later that kind of question hardly mattered anyway. In 1947, congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act outlawing secondary boycotts (boycotts of union companies that do business with a struck company), removing government protection for wildcat (unofficial) strikers, and allowing the president to force workers back to their jobs if he feels that their strike "imperils the national health". The phenomenon of the General Strike came to an abrupt end.

In the aftermath, the Teamsters local withdrew from the central labor council (and not long after, the national Teamsters withdrew from the AFL). Voters elected a labor slate of candidates for the City Council in '47, but not enough to get a majority, and the winners didn't work very well as a team, and were voted out a few years later. Oakland changed dramatically after the war, demographics changed, the beginnings of civil right struggles emerged, but worker control was not on the agenda.

Found at the Oakland History Room.

If you're interested in the Oakland general strike, I'd recommend Chris Rhomberg's No There There. Online you can listen to a nice KPFA documentary on the strike that features interviews with participants and more on the historical context that led to the strike. Also, check out longshoreman and publisher Stan Weir's account of the strike at the very cool libcom.org or Dick Meister's summery on ZNet.

Striking department store clerks, photo from the Oakland Museum of California.

In the first few days of December 1946, retail workers at Hastings' and Kahn's department stores, across the street from each other where Broadway meets Telegraph, had been on strike for more than a month. Most of the workers were women. Their pay was shitty, less than $16 a week, and worse, they were subjected to an absurd procedure where they had to show up to work first thing in the morning, and then wait in the basement (unpaid), until they were called to the floor to work. A clerk could easily be stuck in the basement all morning, or even all day.

The Teamsters local had supported the retail workers strike from the beginning. They refused to deliver anything to the struck stores. (When I was at the Labor Archives, I even saw minutes from the Teamsters Local 70 meeting showing a member being expelled for trying to deliver to Kahn's in November.) The local NAACP and National Negro Congress publicly supported the striking workers. And union laborers had stopped painting and construction of a new elevator at Kahn's in solidarity.

On the business side, the Oakland Tribune, then run by republican powerhouse Joe Knowland, advocated a citywide ban of pickets. According to Albert Lannon's Fight or Be Slaves, right-wing city council members were publicly objecting to the use of the word 'scab'. Most detrimentally, the city agreed to send out the police force to escort delivery trucks to the stores, so they could keep stock for the Christmas shopping season.

OPD escorting delivery trucks from the notoriously anti-union company G.I. Trucking. From the Oakland Museum of California.

That move was too much for the local labor council. The night of December 1st, a Saturday, Teamsters patrolled every roadway into Oakland to keep the delivery trucks away, and the labor council organized members to use their cars to block the parking spaces surrounding the effected stores. Several hundred picketers came out in the middle of the night to keep the scabs out.

Cops block the street to keep strikers out. From the Oakland Museum of California

At 4 in the morning the cops started towing the strikers cars and blocking off sections of Broadway, Telegraph, and San Pablo. When they waved the streetcars through their police line at 6:30 Sunday morning, a driver told the cops that he'd never crossed a picket line, got out of the car and removed its control box, causing an immovable backup along the streetcar line. The general strike was on, although it was another day before the whole city was out.

Tribune clipping from the Oakland History Room.

At a long and fevered meeting of various local AFL union leaders Sunday afternoon (the clerks were affiliated with the AFL), Teamsters pledged that because of the strikebreaking deliveries, they would shut down work in the East Bay starting Monday. Every other union but the milk truck drivers' agreed, and the milk truck drivers only insisted on working in order to get milk to local hospitals. Labor leaders went on the radio to declare Monday a 'work holiday' and to call everyone downtown, to the center of the strike, to show their support.

From the Oakland Museum of California.

At the peak, as many as 30,000 people were packed into the rainy downtown streets. The mood was excited to say the least. Bars were allowed to stay open, but they were only allowed to serve beer, and were told to turn their jukeboxes out to face the street, where people were literally dancing. All AFL building trades were shut down. All East Bay newspapers were shut down. Buses, streetcars, greyhounds, taxis, and trucking were stopped. Gas stations were closed too. Hotels, movie theaters, and larger restaurants and grocery stores were shut.

The picture's pretty blurry, but can you make out those huge grins? From the Oakland Museum again.

I've read conflicting stories on this, but from what I understand, the CIO, the second-largest umbrella union organization in Oakland, had offered their support the night before the strike. They were patently turned down. AFL leaders didn't want to be associated with the CIO whose on-the-ground organizers were largely communist. Robert Ash, the head of the labor council was quite progressive, but balked at working together, imagining headlines in the paper saying "Reds cause Anarchy Downtown" and so forth. Besides the communist associations, the AFL and CIO were rivals not comrades. Working directly with the CIO would have brought about ugly repercussions from national AFL leadership. The CIO honored picket lines anyway, and finally, on the third day of the strike, called for a general meeting to vote on whether to walk out themselves. A CIO walkout would have cut off gas and electricity to most of the city. At this suggestion, Oakland's city manager was ready to settle.

But the unions had lost the upper hand. The national vice president of the Teamsters, Dave Beck, told the local to withdraw from the general strike. He didn't support revolution, and apparently, the strike was developing that flavor. Rumors circulated that Governor Earl Warren was going to send in the National Guard, and the mayor had declared a state of emergency.

Instead of holding their ground, the union negotiated with Oakland's city manager only for an agreement that police would not be used to break strikes. There was no settlement for the department store clerks (who stayed on strike for eight more months, and then had to settle for a weak contract before they finally negotiated a better deal and a closed union shop in May of '47). There was certainly no attempt to make structural change in the city. Robert Ash from the Labor Council admitted later, in retrospect, that had they held out, they could have had more. Maybe they could have gotten the whole right-wing city leadership to resign.

But even that laudable goal suffers from a failure of imagination. Workers owned the city for those three days. They could have done anything. On the other hand, what can you do when you suddenly control your own world? When you have the power to rearrange everything, if only you can agree with tens of thousands of others who share that power? Who knew what to do with complete worker control of a city?

A year later that kind of question hardly mattered anyway. In 1947, congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act outlawing secondary boycotts (boycotts of union companies that do business with a struck company), removing government protection for wildcat (unofficial) strikers, and allowing the president to force workers back to their jobs if he feels that their strike "imperils the national health". The phenomenon of the General Strike came to an abrupt end.

In the aftermath, the Teamsters local withdrew from the central labor council (and not long after, the national Teamsters withdrew from the AFL). Voters elected a labor slate of candidates for the City Council in '47, but not enough to get a majority, and the winners didn't work very well as a team, and were voted out a few years later. Oakland changed dramatically after the war, demographics changed, the beginnings of civil right struggles emerged, but worker control was not on the agenda.

Found at the Oakland History Room.

If you're interested in the Oakland general strike, I'd recommend Chris Rhomberg's No There There. Online you can listen to a nice KPFA documentary on the strike that features interviews with participants and more on the historical context that led to the strike. Also, check out longshoreman and publisher Stan Weir's account of the strike at the very cool libcom.org or Dick Meister's summery on ZNet.

Happy Loving Day

The supreme court finally struck down miscegenation laws 40 years ago, on this day. Happy Loving Day everybody!

(Found on metafilter.)

(Found on metafilter.)

Labels:

1960s,

holidays,

interracial,

love,

supreme court

6.07.2007

THIS IS A STRIKE support our CAUSE - The Oakland General Strike

General Strike! The photo at right shows police milling around an injured shopper in front of a struck Oakland department store. Headline at left refers to a nationwide coal miners strike. This clipping is from the Labor Archives and Research Center at SFSU.

Someone with my politics (anarchist, idealist) tends to think of the general strike as a kind of labor-movement Excalibur, whose ass-kicking powers were so great that it could blind King Arthur's enemies simply by being drawn from its scabbard. (In this problematic analogy, King Arthur = The People.)

A general strike is the ultimate exercise of worker solidarity and worker power and basically, it happens like this: everyone (well, almost everyone), in every industry, stops working until their collective demands are met. One hopes that their demands go beyond asking for better pay or other simple benefits, and begin to address the big problems that go with a society where a few people own everything and do nothing, and others own nothing and do all the work.

And if that is your idea of the purpose and potential of general strikes, then it's clear that they haven't been very successful. Part of the problem though might be that there isn't always a clear purpose, even if there is a lot of potential. In the case of Oakland's 1946 general strike, we had an unbelievable potential power. I'm not so clear on the purpose.

I have so much to say about the Oakland strike, I'm going to split this into a few entries. Here's part 1, the context:

The Bay Area had gained half a million people between 1940 and 1945, when immigrants from around the country flooded in to find work in the war industries (mostly shipbuilding) centered here. The East Bay was so packed, there was nowhere to put everyone. I love the image in Marilyn S. Johnson's book The Second Gold Rush, a quote from an Oakland police captain saying in 1942, "Hundreds of men, women, and children [are] sleeping nightly on outdoor benches in public parks, in chairs in all night restaurants, in theatres, in halls of rooming houses, in automobiles, even in the City Hall corridors." Even with so many people, there were labor shortages. Between the shipyards and the businesses that supported them, there was an almost insatiable need for workers.

But a year after WWII ended, Oakland's economy had already started to wobble. Soldiers came back to a new and newly crowded Bay Area looking for jobs just as the war industries were beginning to contract. And the population boom and economic stressors weren't the only pressures. The need for labor had overruled some long standing social and political rules here and everywhere, most obviously, many more women, including for the first time middle class women, started working in factories and other industries. And Black immigrants to the Bay started to integrate the segregated neighborhoods and jobs here. Returning soldiers too had been transformed by their battlefield experiences. Maybe they expected to be able to make changes that hadn't seemed possible before.

Working conditions hadn't been great during the war, but most unions had signed patriotic No Strike pledges. After the war, business leaders and government officials found it impossible to stuff a broadening political agenda back into a box. In '46, a massive strike wave spread around the country (and internationally). The rail and coal mining industries were debilitated by strikes that year, and a number of cities held general strikes.

I found a newsreel that nicely captures the panic that industrialists felt about the rail strike at archive.org.

In this context, of a country and world that was changing by the second, where worker power seemed possible and real, and let's face it, where communists were all over the place, the idea of shutting down a city wasn't just a fantasy. At least, that's what I understand from what I've read.

Next time I'll post about the strike itself. I've got some links to original accounts and a nice documentary too. Stay tuned.

6.04.2007

Hometown

On the corner of East 34th and 13th Avenue is the house I grew up in. If you drive by now you'll find graying paint covering the pink that I remember, and the owners have replaced the wooden window frames; some were rotting even when I lived there. They've cut back the ivy in the front yard and put up some chain link. Otherwise, it's pretty much the same old house it was when my family left 20 years ago, surrounded by a bunch of other little family houses, all looking pretty similar but cozy.

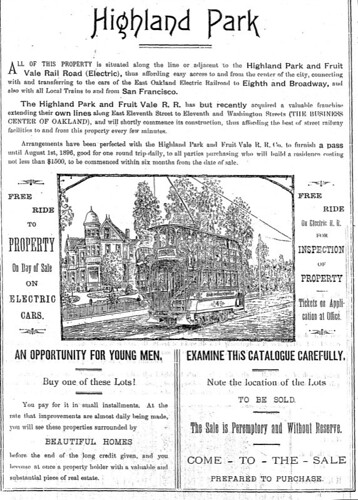

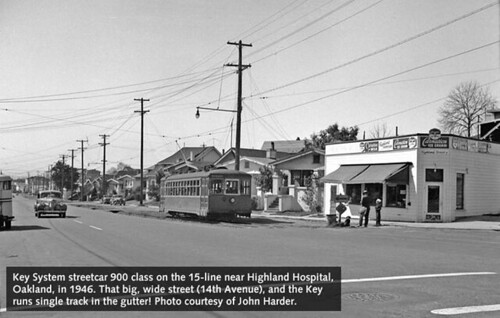

The house was built in 1921, part of a construction boom that was still reverberating through Oakland 15 years after the San Francisco earthquake. When the city burned, residents turned to less developed or agricultural land in the East Bay where forward thinking real estate developers had already bought up (or squatted) massive tracts in hopes of making a lot of cash. After buying the land, the developers would generally build a few impressive houses, and then run a streetcar to the new 'neighborhood' to bring people in.

My old neighborhood, including the lot my house was built on, were initially owned by banker E.C. Sessions who envisioned high-class, wide lotted properties gathered around the central hill that is now under Highland Hospital. His double-deckered horse-drawn street cars traveled up 14th Avenue (called "Commerce" at the time) and then cut over to Fruitvale.

Unfortunately for E.C., he was ahead of his time, and ended up selling off his land in small parcels before the neighborhood took off in the 20s. (Highland Hospital, a few blocks away, and the beloved Parkway Theatre down the street on Park Blvd. were built in the '20s too.)

My parents moved to the house around 1970, and paid $200 a month for three bedrooms, a living room, formal (if small) dining room, and a rumpus room downstairs, along with the backyard and its decrepit gazebo. Oakland had changed a lot from the pastoral (and profitable) oasis that developers like E.C. Sessions had imagined. In my neighborhood, the two story streetcars had long been replaced by more uniform Key System trains, which subsequently disappeared too. The city as a whole had never fully recovered from a post-WWII economic downturn, and because of the efforts of dozens of civil rights groups, it was just beginning to grow out of long-standing policies of racial discrimination.

By the time I was school aged, Oakland had a reputation as a crime center. Crack was beginning its ascent, and I'm sure even my not-so-deep section of East Oakland was impacted. But my sense of my home was that it was safe and that it was stable. My young neighbors and I hid in the bushes of my house to throw berries at passing cars, played football in the parking lot around the corner, and walked back and forth to the liquor store up the street for Now-and-Laters and Chick-o-Sticks.

Like anybody's hometown anywhere, Oakland is, to me, the place I know in and out, the place I can tell my kids about when I'm trying to help them understand my sense of the world. Lucky for me, and for them, they live here too, so they can compare their stories to my stories, and find their own adventures in a spot where they have roots.

I'm wanting to understand the history of this place in part because I'm a parent, and getting how things happened seems more important now, so I can do things right for them. I want to get the things that people did right, and avoid the things folks did wrong. And I want to be able to thank the people who gave me all the things I love about this city and this world. So I'm mostly going to write about activists and radicals and movements. Since I'm not any kind of expert, I'll just be writing as I'm learning. If you've got something to share about the activist history of the Bay Area, I'd love to hear from you. Thanks for reading.

Thanks too for photos on this site: the Highland Park advertisement is from the Oakland History Room, and the Key Line streetcar came from keyrailpics.org, an awesome photo site full of Bay Area streetcar photos.

The house was built in 1921, part of a construction boom that was still reverberating through Oakland 15 years after the San Francisco earthquake. When the city burned, residents turned to less developed or agricultural land in the East Bay where forward thinking real estate developers had already bought up (or squatted) massive tracts in hopes of making a lot of cash. After buying the land, the developers would generally build a few impressive houses, and then run a streetcar to the new 'neighborhood' to bring people in.

My old neighborhood, including the lot my house was built on, were initially owned by banker E.C. Sessions who envisioned high-class, wide lotted properties gathered around the central hill that is now under Highland Hospital. His double-deckered horse-drawn street cars traveled up 14th Avenue (called "Commerce" at the time) and then cut over to Fruitvale.

Unfortunately for E.C., he was ahead of his time, and ended up selling off his land in small parcels before the neighborhood took off in the 20s. (Highland Hospital, a few blocks away, and the beloved Parkway Theatre down the street on Park Blvd. were built in the '20s too.)

My parents moved to the house around 1970, and paid $200 a month for three bedrooms, a living room, formal (if small) dining room, and a rumpus room downstairs, along with the backyard and its decrepit gazebo. Oakland had changed a lot from the pastoral (and profitable) oasis that developers like E.C. Sessions had imagined. In my neighborhood, the two story streetcars had long been replaced by more uniform Key System trains, which subsequently disappeared too. The city as a whole had never fully recovered from a post-WWII economic downturn, and because of the efforts of dozens of civil rights groups, it was just beginning to grow out of long-standing policies of racial discrimination.

By the time I was school aged, Oakland had a reputation as a crime center. Crack was beginning its ascent, and I'm sure even my not-so-deep section of East Oakland was impacted. But my sense of my home was that it was safe and that it was stable. My young neighbors and I hid in the bushes of my house to throw berries at passing cars, played football in the parking lot around the corner, and walked back and forth to the liquor store up the street for Now-and-Laters and Chick-o-Sticks.

Like anybody's hometown anywhere, Oakland is, to me, the place I know in and out, the place I can tell my kids about when I'm trying to help them understand my sense of the world. Lucky for me, and for them, they live here too, so they can compare their stories to my stories, and find their own adventures in a spot where they have roots.

I'm wanting to understand the history of this place in part because I'm a parent, and getting how things happened seems more important now, so I can do things right for them. I want to get the things that people did right, and avoid the things folks did wrong. And I want to be able to thank the people who gave me all the things I love about this city and this world. So I'm mostly going to write about activists and radicals and movements. Since I'm not any kind of expert, I'll just be writing as I'm learning. If you've got something to share about the activist history of the Bay Area, I'd love to hear from you. Thanks for reading.

Thanks too for photos on this site: the Highland Park advertisement is from the Oakland History Room, and the Key Line streetcar came from keyrailpics.org, an awesome photo site full of Bay Area streetcar photos.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)